D.C. has a complicated relationship with speed cameras. Research shows that speed cameras are an important tool to reduce crashes and traffic fatalities, especially as a complement to underlying road design improvements, and neighborhood residents frequently request them to slow traffic in dangerous areas. Automated cameras can also help reduce racially biased enforcement and provide consistent enforcement in areas where it may be impractical or unsafe for police officers to monitor a location in person.

Despite the safety benefits of speed cameras, however, speed cameras remain controversial in D.C., as some drivers—and at least one councilmember—have questioned whether the fines are too high. Automated traffic enforcement measures like speed cameras and red-light cameras are can generate a lot of revenue to city governments with little effort after the initial installation. The District’s speed camera revenues have increased substantially over time as the program has been fully rolled out and expanded, and AAA and many motorists complain that their placement and fine levels have more to do with generating revenue than saving lives. And because highest revenue cameras are on commuter routes, some think these cameras have been purposefully put in these locations to generate maximum revenue from commuters. Recently publicized errors in enforcement have further eroded trust in the process.

Full and complete crash data for the city is not available, but using available data from 2008-2017, we find that many of the highest-revenue speed cameras are located in areas with high speed-related crash activity. At the same time, the presence of speed cameras alone does not appear to have addressed the underlying issues at some of D.C.’s most dangerous intersections, suggesting that the city could take additional measures to improve street safety and reduce crashes.

Speeding kills—but cameras can help.

Speeding increases the severity of injuries in a crash and may increase the likelihood of a crash occurring. While fatal crashes can occur at any speed, the risk of a pedestrian being killed sharply increases when the speed of the car at the time of the crash is 30 mph or higher. In D.C., speed is a factor in over half (59 percent) of fatal crashes, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.[1]

Speed cameras are effective at reducing the incidence of speeding and crashes.[2] For example, a 2002 study of D.C.’s early speed camera system found that travel speeds were reduced by 14 percent at speed camera sites, and the proportion of vehicles exceeding the speed limit by more than 10 miles per hour decreased by 82 percent.[3]

Automated speed enforcement has several advantages over officer-enforced speed enforcement. The most obvious is the ability to cover larger enforcement areas at lower cost. One of the main reasons drivers do not commit traffic violations is the perceived risk of being caught. Cameras can also be placed at locations that may not be ideal places for police officers to stop, potentially reducing accidents and congestion.

Furthermore, officer-enforced speed enforcement is not enforced uniformly, and officers’ decisions around who will be cited and what citation they will be given can increase racial disparities. In a study in Florida, white drivers were more likely than Black or Hispanic drivers to be cited for speeding nine miles per hour over the speed limit, a level where fine amounts are relatively low. Although the placement of speed cameras can still introduce biases that lead to disparate outcomes, camera enforcement eliminates the introduction of officer-related bias.

Mapping speed-related crashes and speed camera locations in D.C.

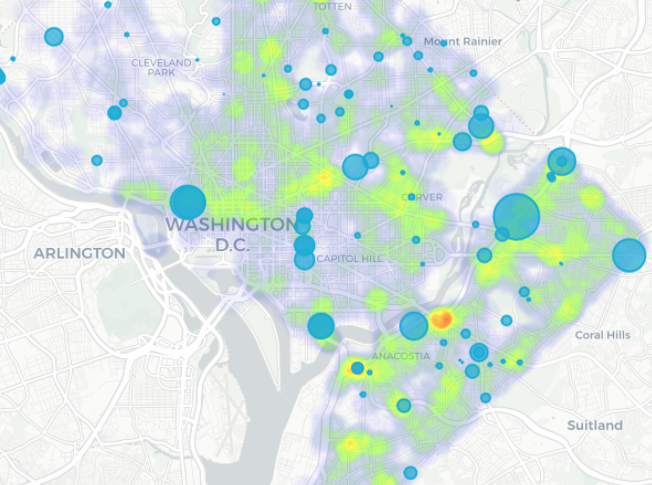

The District issued collected $194.1 million worth of speeding tickets in fiscal year 2017. As the map below shows, many cameras were placed in areas that have had a large concentration of speed-related crashes between 2008 and 2018. While crash data used here is the most extensive data available to the public,[4] it does not appear to be comprehensive; it does not include crashes with missing or incomplete data, and at the time of writing, crashes also appeared to be underreported for 2008, 2009, and 2017, based on comparisons to other published reports on crash data for these time periods. However, this approach does give us a sense of which locations continue to be dangerous, though it may underrepresent the number of crashes in some areas.

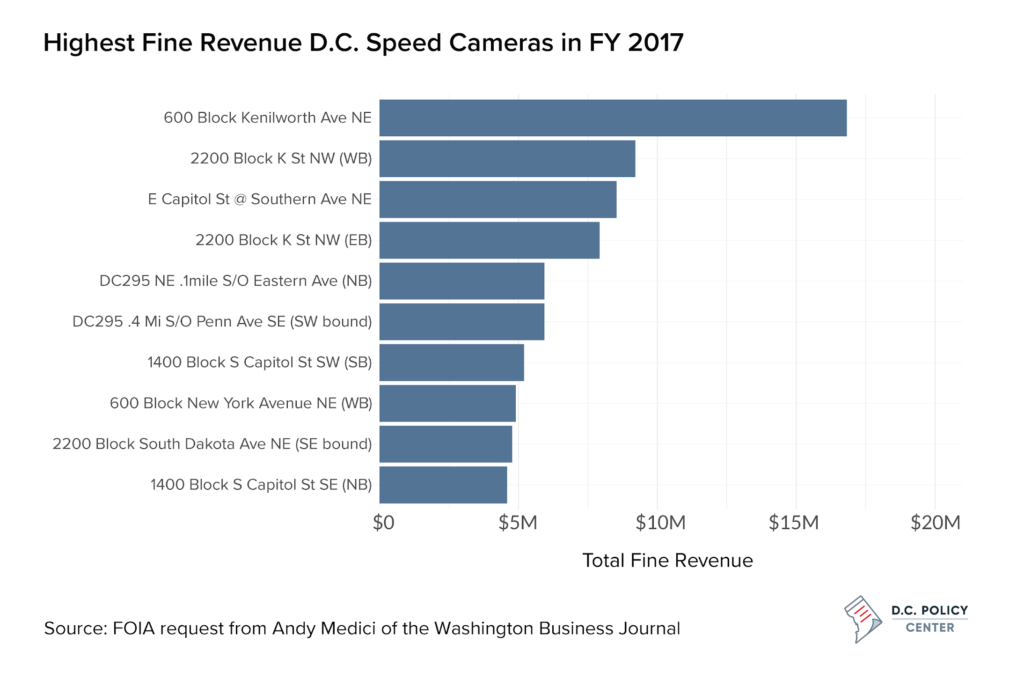

The highest-revenue speed camera, located on the 600 block of Kenilworth Ave (Southbound), earned $16,817,950 in fine revenue in fiscal year 2017. This camera is placed on the feeder road next to 295 and is adjacent to a residential neighborhood. The speed limit on Interstate 295 is 50 mph, while the speed limit on Kenilworth Avenue is 25 mph where it meets Intestate 295; later, the speed limit increases to 35 mph. These rapid changes in speed limits, combined with confusing signage may explain the relatively high fine revenues compared to other speed camera enforcement locations in the city.

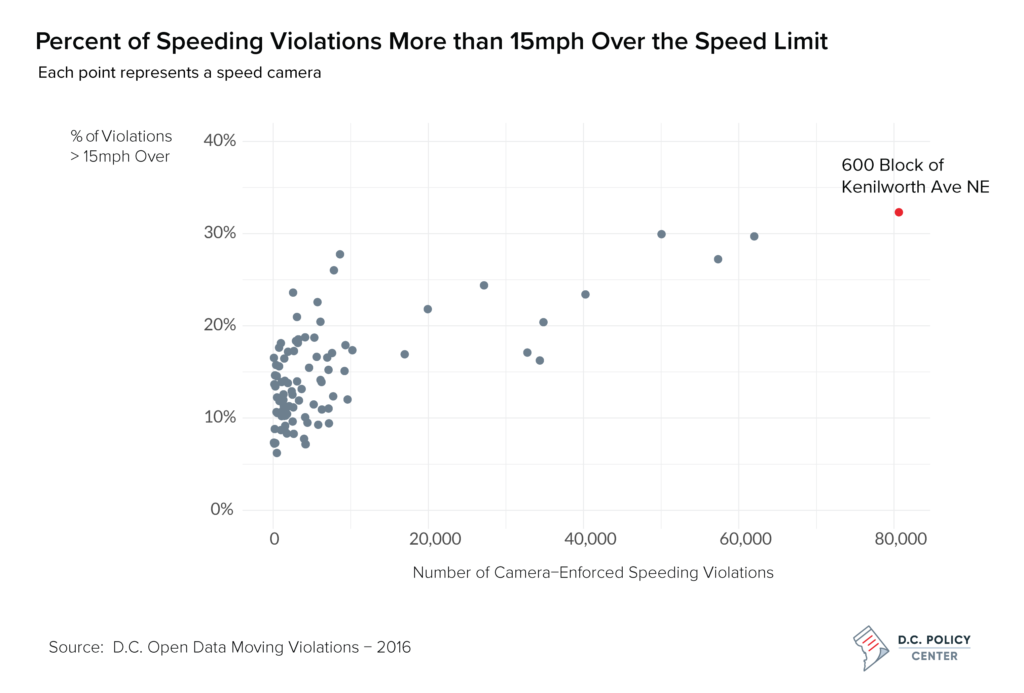

At the 600 Block of Kenilworth Ave NE (Southbound), 33 percent of speed violations were more than 15 miles per hour over the speed limit, compared to the median of 14 percent. The chart below shows just how much of an outlier the Kenilworth Avenue speed camera is, both in terms of the number of speeding violations and in terms of violations more than 15 mph over the speed limit; this could suggest a failure of the placement of the current speed limit signage, if drivers are unaware of the speed limit change from 50 mph to 25 mph. And whether due to poor signage or other factors, the high number of speeding violations at this location indicates both that speeding is a still problem, and that it has not been solved by the presence of this camera.

The Kenilworth Avenue camera—and its extremely high revenues for the city—has made it a frequent point of contention for drivers who argue that the location is simply a “speed trap”, with continued high fines indicating that the camera is not leading to safer driving. The high revenues from the Kenilworth Avenue camera and other locations near the District’s border also can appear to be placed on commuter routes in order to generate maximum revenue from workers commuting into D.C.

On November 25, 2017, a pedestrian was struck and killed by a car near this intersection. Shortly after her death, ANC 7D commissioners wrote a letter outlining specific issues in ANC 7D. Residents have expressed concerns about safety due to blocked crosswalks and speeding, but community leaders in ANC 7D have doubts that this camera has improved safety.

Despite concerns, a majority of D.C. residents support speed camera enforcement

People in D.C. want safer streets, but do not always agree that speed cameras are the best way of achieving this. In news coverage and on neighborhood listservs, residents often suggest that speed cameras are primarily used to raise revenue, but surveys show that most D.C. residents support speed cameras.

Speeding is generally viewed as unacceptable behavior, yet it is still common. In a 2016 AAA survey, 88.3 percent of drivers considered it unacceptable to drive 10 miles per hour over the speed limit on a residential street, yet 45.6 percent reported having done so in the previous 30 days. In this survey, 43 percent of respondents supported using automated speed camera enforcement in residential neighborhoods.

While there are many vocal opponents of speed camera enforcement, a November 2012 survey from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) found that 76 percent of D.C. residents favored speed camera enforcement, with 90 percent of non-drivers favoring speed camera enforcement. Among drivers cited for speeding, 59 percent believed their citation was deserved. Although there is evidence supporting the safety benefits of speed cameras, 35 percent of those opposed to speed cameras believed that cameras were intended to raise revenue rather than enhance safety.

Best practices for speed cameras

Federal Highway Administration guidance suggests that speed camera sites should be selected using factors such as crash risk, crash history, citizen complaints, and proximity to pedestrians. School zones, residential neighborhoods, and major roads are common sites for speed cameras. It also suggests that cameras should be evenly distributed throughout a jurisdiction to avoid bias.

The best insight into the placement of cameras—and their effectiveness—comes from the regular reports DDOT and MPD are required to submit a report to the D.C. Council. These reports include a list of each speed camera in the District; an analysis of the speed camera’s nexus with safety; and, if no nexus with safety can be identified, a justification by MPD regarding the speed camera’s location.

D.C. has performed safety studies at current and potential speed camera sites, incorporating data on crashes and speeding. These studies include the reasons that a specific site is included, such as location in a residential neighborhood or proximity to a school or other pedestrian generator. Generally, DDOT’s studies indicate that D.C. has followed best practices for speed camera enforcement.

On the other hand, there have been inconsistencies and errors in the execution of the speed camera program, which can erode trust in the program. A recent investigation by WUSA9 found that signs informing drivers of the presence of speed cameras were inconsistent, with signs sometimes misplaced or even absent. In 2016, WTOP reported that a speed camera unit was criticized for its unsafe placement. On local listservs, residents express concerns over speed cameras, such as suspected “speed traps” and the ineffectiveness of existing speed cameras at improving safety.

One answer might be to improve signage while also making cameras more mobile, as networks of mobile cameras are shown to be more effective than having fixed locations in changing driver behavior. While fixed speed cameras may have a limited “halo” effect, resulting in speed reduction in areas surrounding speed cameras, an extensive network of speed cameras appears to change behavior along the entire commute path. In neighboring Montgomery County, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) studied speeding, crashes, and traffic fatalities to assess the effectiveness of the Montgomery County speed camera enforcement program after they added “speed camera corridors”, where cameras are not in a fixed location and may move along a corridor. IIHS found that the likelihood of drivers exceeding the speed limit by more than 10 miles per hour was reduced by more than 59 percent after speed cameras were installed. They found that injuries and fatalities also decreased on roads without speed cameras.

Another improvement would be to reduce delays in receiving tickets. In one example, a driver told NBC4 that he received a speeding ticket every day for 12 days at the Kenilworth Avenue location before he received the first ticket in the mail, leading to $1,500 in fines. Delays like this feel unfair to drivers and reduce the effectiveness of the speed cameras, as people need to know they’re there and receive the fine promptly to affect behavior.

Finally, safety discussions could be better informed with better data. Speed camera revenue data are not readily available and must be requested through freedom of information requests. Under the District’s open data protocol, this data should be public. It would also be useful for researchers to have documentation of any changes or updates made to the data, as posted data sets can be updated without a record of what has changed. More complete data would also help researchers, residents, and transportation advocates understand which locations require additional safety measures; the car crash data is, by DDOT’s own admission, incomplete due to the exclusion of incomplete records, which limits the ability to locate all areas of crash activity in the District.

What else can D.C. do to reduce speeding?

While speed enforcement is important, persistent speeding indicates that speed cameras alone have not made some locations safer, suggesting the need for other countermeasures. In addition, the District can reduce the incidence of speeding by better road design and engineering, and more intensive education.

Road design changes can range from relatively minor adjustments, like pavement markings, speed humps, and signage, to more extensive changes, like medians, bike lanes, and crosswalks, to discourage speeding and improve safety conditions. Focusing on road design improvements can address the underlying causes of unsafe roads and make the road safer for all road users. DDOT’s site visits to intersections or roadways with highest incidence of crashes find safety issues that include signal timing and phasing, ADA compliance, sidewalk needs, bike lanes, and clarifying signage. Some of these require significant work, but others are relatively minor improvements. These changes are especially needed in low-income neighborhoods, where pedestrians are more likely to be injured or killed due to more dangerous road conditions such as increased traffic volume and the presence of arterial roads and four-way intersections.

In terms of the highest-revenue camera at the 600 block of Kenilworth Avenue, community members within ANC 7D suggested safety improvements to DDOT, some of which DDOT has committed to addressing. These improvements include traffic calming, crosswalk installation, and pavement markings, which would all likely improve safety in the area.

A map of the requested safety improvements listed in ANC 7D’s December letter to DDOT, made by Justin Lini. (Source)

Speed cameras can be an important tool to support design solutions, reduce enforcement bias, and improve street safety—but implementation details matter.

Speed cameras are a valuable tool, but they should be used in concert with safer street design and best practices in implementation to improve safety and maintain the support of the local community.[5] The public can identify locations where speed cameras should be deployed and provide feedback to the program. Revealing camera locations does make drivers aware of the camera locations, but this also can improve speed enforcement as drivers know the areas of enforcement. While some drivers may only slow down where they know there are cameras, only to accelerate shortly after, there is evidence that combining public awareness campaigns with enforcement can be most effective.

Public awareness of camera locations is also important for transparency and fairness. The D.C. government should ensure that they are transparent with the public, communicating about program changes and evaluating awareness and attitudes about speed cameras, as well as public awareness and education about speeding. Education around speeding may also help residents understand why there is a need for speed cameras in the first place: Many drivers overstate their driving ability, and may hold counterproductive or even dangerous views about driving safety.

Speed camera enforcement penalties can change behavior and make roads safer, but fines should not be overly punitive; there is no evidence that additional penalties on top of fines enhance safety, for instance. Currently, low-income residents are harmed more by fines, and one study found that higher-income individuals were more likely to break the law while driving, suggesting that fines do not have the same impact on their behavior (while another found that high-income drivers were more likely to speed). A reduction in penalties or relief specifically for low-income residents would be one method to prevent fines from having an outsized impact on more vulnerable populations. An example of this is “day fines,” which are scaled in relation to a person’s wages and ensure that fine amounts take into consideration ability to pay.

About the data

Fiscal Year 2017 Camera Enforcement Revenue data: Obtained through a FOIA request by Andy Medici of the Washington Business Journal.

Speed camera locations: D.C. Open Data, Camera Enforcement Locations.

Moving violations data: D.C. Open Data, moving violations issued in October 2016 through September 2017 (monthly datasets).

D.C. Crash data: D.C. Open Data, Crashes in DC and Crash Details Table datasets for 2008-2017. This data is incomplete as it does not include crashes with missing or incomplete data; at the time of writing, crashes also appeared to be underreported for 2008, 2009, and 2017, based on comparisons to other published reports on crash data for these time periods.

Fatal crash data: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) and State Traffic Safety Information (STSI).

Notes

[1] National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS).

[2] In 2017, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) recommended the use of speed cameras to address the role that speed plays in crashes and fatalities.

[3] Retting, R., & Farmer, C. (2003). Evaluation of Speed Camera Enforcement in the District of Columbia. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1830, 34–37.

[4] D.C. Open Data “Crashes in DC” and “Crash Details Table” datasets for 2008-2017.

[5] Federal Highway Administration guidelines identify three types of countermeasures that can be used to mitigate speeding: engineering, education, and enforcement.

Simone Roy is a Research Associate at the D.C. Policy Center.