The D.C. Policy Center report “Taking Stock of the District’s Housing Stock: Capacity, Affordability and Pressures on Family Housing” provides a comprehensive picture of the District’s housing stock to explore a longer-term view of housing affordability, especially for low and middle-income families in the District of Columbia.

Taking Stock creates a new dataset of the District’s housing stock from multiple data sources. It uses this information to estimate the number of housing units in the city, the types of buildings that contain housing units, and the capacity of each unit. It also develops a methodology to estimate the potential affordability of each unit.

The report finds that a significant pressure on the District’s housing market is the fierce competition for larger units from affluent singles and couples. The District has many more larger units than families who could live in them; however, affluent singles and couples occupy many of these. Meanwhile, there are not enough smaller units to satisfy the demand from small households. Furthermore, land-use and zoning policies restrict the amount and mix of housing supply in many parts of the city with public and private amenities. Other parts of the city have affordable family-sized units but lack the resources families need to thrive. Both dynamics limit the city’s inclusiveness, amplifying gentrification, economic segregation, and the loss of low- and middle-income families.

Below is a summary of the report and its key findings and conclusions. Click here to read the full report, or download the report as a PDF.

Housing policies are central to the inclusiveness of a city.

Housing defines, in large part, how residents share the wealth created by a city and how they access its assets and amenities. Where we live deeply affects our quality of life and the opportunities available to us and our children, especially jobs and better schools. How we invest in a neighborhood determines the desirability of the housing stock in that neighborhood and how we regulate our housing markets can shape who stays in the city and who leaves. Public policies that control the housing supply and public investments in amenities and services such as schools, transportation, and infrastructure can play roles equally strong as private wealth in defining the demographic make-up of a city.[1] Population growth and demographic changes continually play out through the housing market, and when housing is constrained, these forces further amplify gentrification, economic segregation, and displacement.

The District has experienced tremendous population growth in the last twenty years but, along with growth, the city has also seen dramatic changes in its demographic and socioeconomic make-up. The city is richer and whiter, less inclusive, and more segregated. These changes are partly attributable to the composition of the city’s housing stock, and especially the scarcity of family-sized units affordable to low and middle-income families.[2] The lack of housing options is pushing low and middle-income families out of the city and increasing economic segregation. [3][4] We know that housing burdens in the District are high and that the housing market does not offer many options to low and middle-income households.[5] But we have paid little attention to how the overall structure of the District’s housing stock—and the market forces and government policy choices that have produced this stock—have played a role in this outcome.

A better grasp of the characteristics of the District’s housing stock can help show where, across what types of housing, and across what price range housing shortages are the most dire. It can also shed light on the extent to which land use policies restrict growth of the housing inventory and help identify ways in which the existing housing stock can be repurposed to meet changing needs. Finally, there an intense policy debate that stems from concerns about affordability (and, in recent days, centered around the city’s Comprehensive Plan update) with views divided between whether relaxing zoning constraints to allow market rate housing can help solve the problem or whether the city should regulate or subsidize the production and preservation of more affordable housing units. Our findings can inform this debate.

The District’s housing stock outside Downtown is spread across low-rise, low-density buildings.

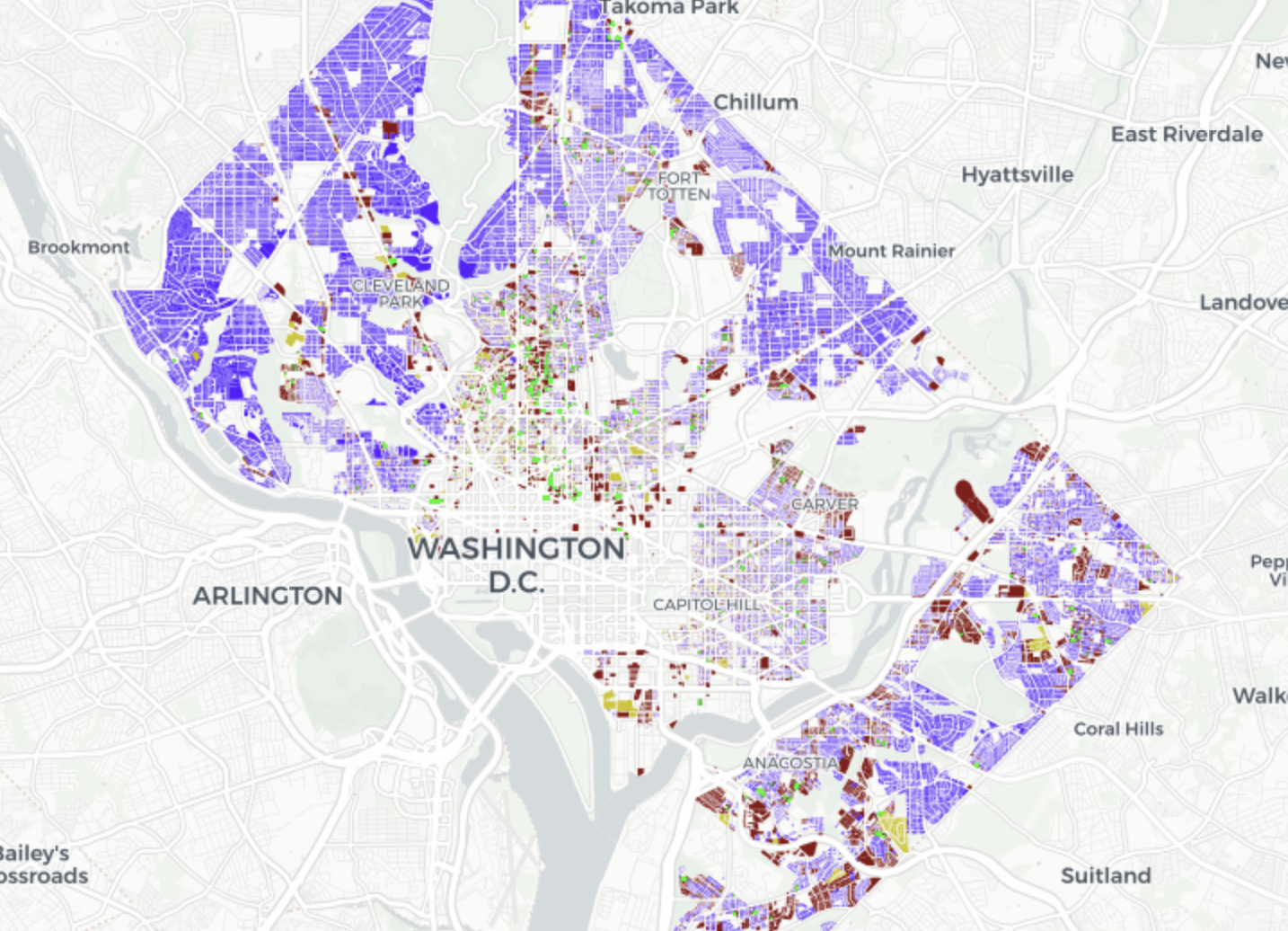

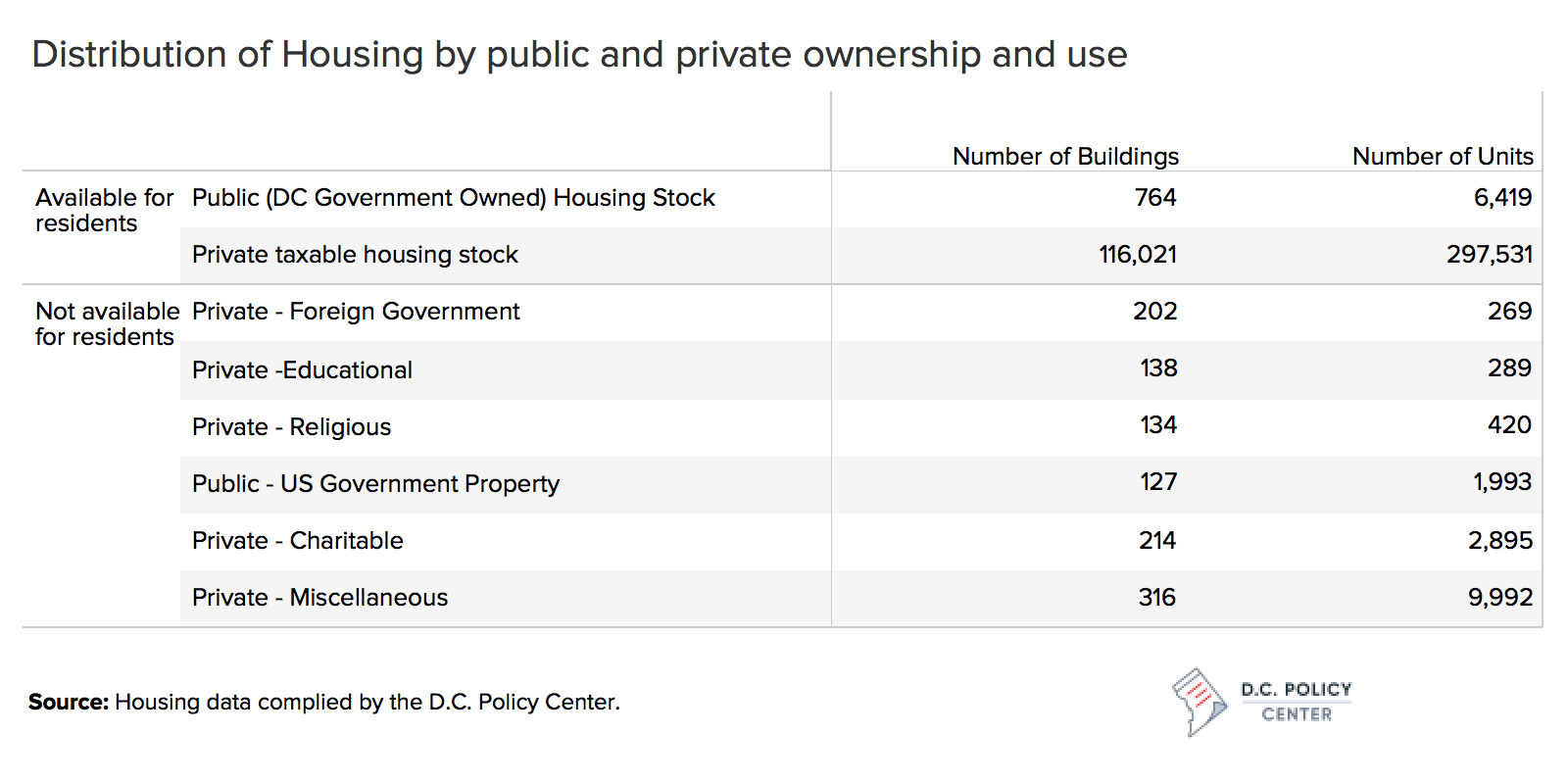

We estimate that there about 319,800 housing units in the District of Columbia spread across 116,781 buildings. But not all these units are available to residents. About 10 percent of District’s housing stock belong to foreign governments, the U.S. government, or are otherwise not available to residents because they are a part of educational, religious, or medical complexes. Excluding these units leaves us with 303,950 units.

The 93,470 single-family units make up only 30 percent of the District’s housing stock, but 80 percent of the residential buildings. The rest of the housing stock is made up of 120,600 rental apartment units, 64,300 condominium units, and 28,600 units in cooperatives, all in squeezed into 23,900 buildings. That is, the footprint of small, single, or double unit buildings in the District is extremely large, giving certain parts of the city a suburban feeling.

For a land-constrained city, the District has set aside a significant amount of land for low-rise, low occupancy housing units. We count only eleven assessment neighborhoods where there are more than five units per building, on average. In another 14 neighborhoods, there are more than two units per building. In the remaining 32 tax assessment neighborhoods, a typical residential unit is a single-family detached home, a semi-detached house, or a row house. This configuration of the housing stock is mostly a creature of zoning and land use regulations. Almost the entirety of Ward 3’s land zoned for residential use is occupied by single-family units. It is the same through large swaths of Wards 2, 4, 5, and 7. Multifamily units are concentrated in the Downtown area and occupy a majority of the residential land in Ward 8.

Source: Data compiled by the D.C. Policy Center. The full-screen map is available here.

Restrictive land use practices that favor single-family units in the District are a major factor of exclusion. Even small changes in the mix of buildings can make meaningful improvements to the inclusiveness of the city. Consider the eight assessment neighborhoods in Northwest (Hawthorne, Colonial Village, Woodley, Foxhall, Burleith, Kent, Spring Valley and Berkley) with an average of one unit per building—all single-family homes. These eight neighborhoods, collectively have 4,876 housing units in 4,748 buildings. Adding just one single low-rise multifamily building with 100 units in each of these neighborhoods would increase their housing units by 16 percent while increasing the number of buildings by 0.2 percent. That is, potentially 800 new families would benefit from the amenities offered by these neighborhoods – good schools, safe streets, access to employment centers—with the addition of just one apartment building per neighborhood.

Home ownership is highest in the Northeast quadrant due to the concentration of seniors.

About a third of housing units in the District (about 103,250 units) are owner-occupied. This is important because whether families own their own home has historically been a factor in whether families are able to accumulate wealth and pass that wealth down between generations, and historical inequities in home ownership have contributed to modern-day disparities in wealth accumulation. The remaining 200,700 units are either rented out or owned and occupied by a person who is not a D.C. resident. Rental apartments make up 59 percent of such units. Condominiums and cooperatives also offer a robust number of units for rent, with 55,554 units recorded as not owner-occupied. 27,000 of the District’s 93,400 single-family units are also potentially rented out.

Source: Data compiled by the D.C. Policy Center. The full-screen map is available here.

The Southeast quadrant has the lowest homeownership rate. Here, renters occupy 82 percent of the 58,340 housing units, (half of which are rentals). The Northeast quadrant has the highest share of housing units occupied by their owners. Concentrated home ownership in the long-standing residential neighborhoods of Hillcrest and the northeast section of Capitol Hill, both of which have about 80 percent of their housing units occupied by their owners, increase the average ownership rate across the Northeast quadrant. Neighborhoods in the Northwest quadrant have 34 percent of all housing units occupied by their owners, but this is due to the greater number of rental housing options across the densely populated Foggy Bottom and the Central City assessment neighborhoods. If we measure ownership across the assessment neighborhood level, we find a median of 50 percent owner-occupied housing. The variation in home ownership across neighborhoods is also large in this quadrant, with neighborhoods west of the Park having over 70 percent owner-occupied housing (Colonial Village, Hawthorn, Woodley, Kent, Spring Valley, American University Park), and under 20 percent in Foggy Bottom and Central City assessment neighborhoods.

The map of housing units by ownership status shows that homeownership is particularly strong along the northeast and northwest borders mainly because of the concentration of senior-owned housing (pink units on the map). The Hillcrest neighborhood in Ward 7, and Michigan Park, Riggs Park, Woodridge, and parts of Brookland in Ward 5, also stand out as having particularly high ownership rates. Homeownership in these neighborhoods can be traced back to 1950s and 1960s, when, in response to school desegregation, the city’s white population started leaving for the suburbs, and provided opportunities for many of the city’s black residents to purchase a home. Some of these homes are intergenerational, and others occupied only by their senior owners, who prefer not to or cannot downsize.

Estimated values increase from east to west.

Across 303,910 housing units available for resident use in the District, the estimated median value is $459 per square foot. If we exclude from this group D.C. Government-owned affordable housing units (6,500 units) and units that are tax exempt because they serve low income families (1,098 units), we see the median income assessment increases to $460 per square foot—a value comparable to what real estate analysts have found.

Condominium units and units in cooperatives are the highest valued housing units on a per square foot basis at $562 per square foot and $513 per square foot, respectively. These units are more likely to be in highly desirable neighborhoods and therefore more expensive. For example, 73 percent of condominium units and 65 percent of cooperatives are in the Northwest quadrant. The values also include professional building management, shared amenities such as a concierge, a high level of building maintenance, and common areas. The median value of single family homes is $396 per square foot. Among single family homes, row houses are the most expensive and semi-detached housing units (clustered in the Northeast and Southeast quadrants) are the least expensive. And 80 percent of single family homes are estimated to have a value between $200 and $500 per square foot.

Estimated values increase from east to west, with some unexpected pockets of affordability (in median prices). East of the river, median assessments are under $234 per square foot across assessment neighborhoods, with the lowest values in Congress Heights ($192) and highest in Hillcrest. West of the Anacostia River, Fort Lincoln is the only neighborhood with a median assessed value under $250 per square foot. Moving farther west, the lowest estimated median values we find are all over $330 per square foot with Chillum, Takoma, and Brightwood offering the best bargains. West of the Park, it is not unusual to see median values over $500 per square foot, the only neighborhood with a median value under $450 being Wesley Heights ($437 per square foot), which includes many senior owned properties. Housing owned by seniors tend to have lower estimated values. The median per square foot value for senior-owned and occupied units is $353, compared to $477 for non-senior homestead properties, and $480 per square foot for properties not occupied by their owners.

Source: Data compiled by the D.C. Policy Center. The full-screen map is available here.

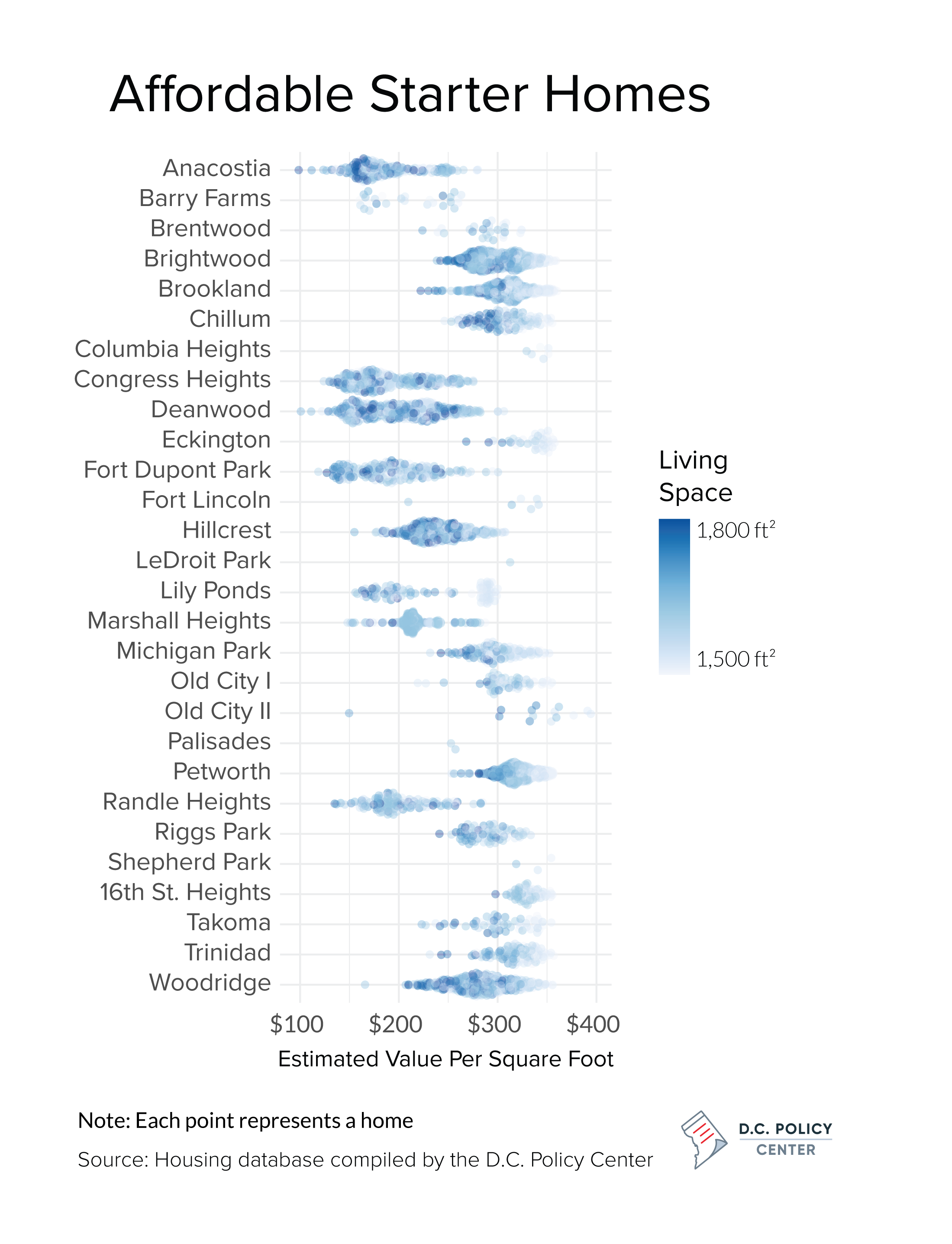

The District has very few starter homes potentially affordable for middle income families.

We found very few single-family homes between 1,500 and 1,800 square foot that could accommodate a family of four and be afforded at or below the Area Median Income (hence, a housing unit that cannot be more expensive than $560,000). Of the 16,900 single family homes that fit this size and number of rooms criteria, only 4,764 properties (28 percent) could be potentially affordable to a family making the Area Median Income. (If one were to include condominiums and cooperatives of this size, this number improves by 1,000 only.) Three-quarters of these units are in the Northeast and Southeast quadrants in seven neighborhoods—Brightwood, Brookland, Petworth, Woodridge, Congress Heights, Deanwood, and Hillcrest. We could find only two such homes west of the Park (out of 3,101 starter homes), none in Capitol Hill (out of 431), just three in Shepherd Park (out of 232 starter homes), and 57 (out of 1952) in the very large Old City I assessment neighborhood (that has more starter homes than any other neighborhood assessment area).

The numbers rapidly get worse at lower income levels. At 80 percent of Area Median Income, we could find only 1,821 starter homes in the District’s housing stock of 303,400 units that are potentially affordable for middle-income families. At 60 percent, we could find only 533 such starter homes. To put this in context, the American Community Survey data tell us that of the 121,101 families in the District of Columbia, about 70,000 families have incomes under $110,000, 51,000 families make less than 80 percent of area median income, and about 41,500 families make 60 percent of Area Median Income or less.

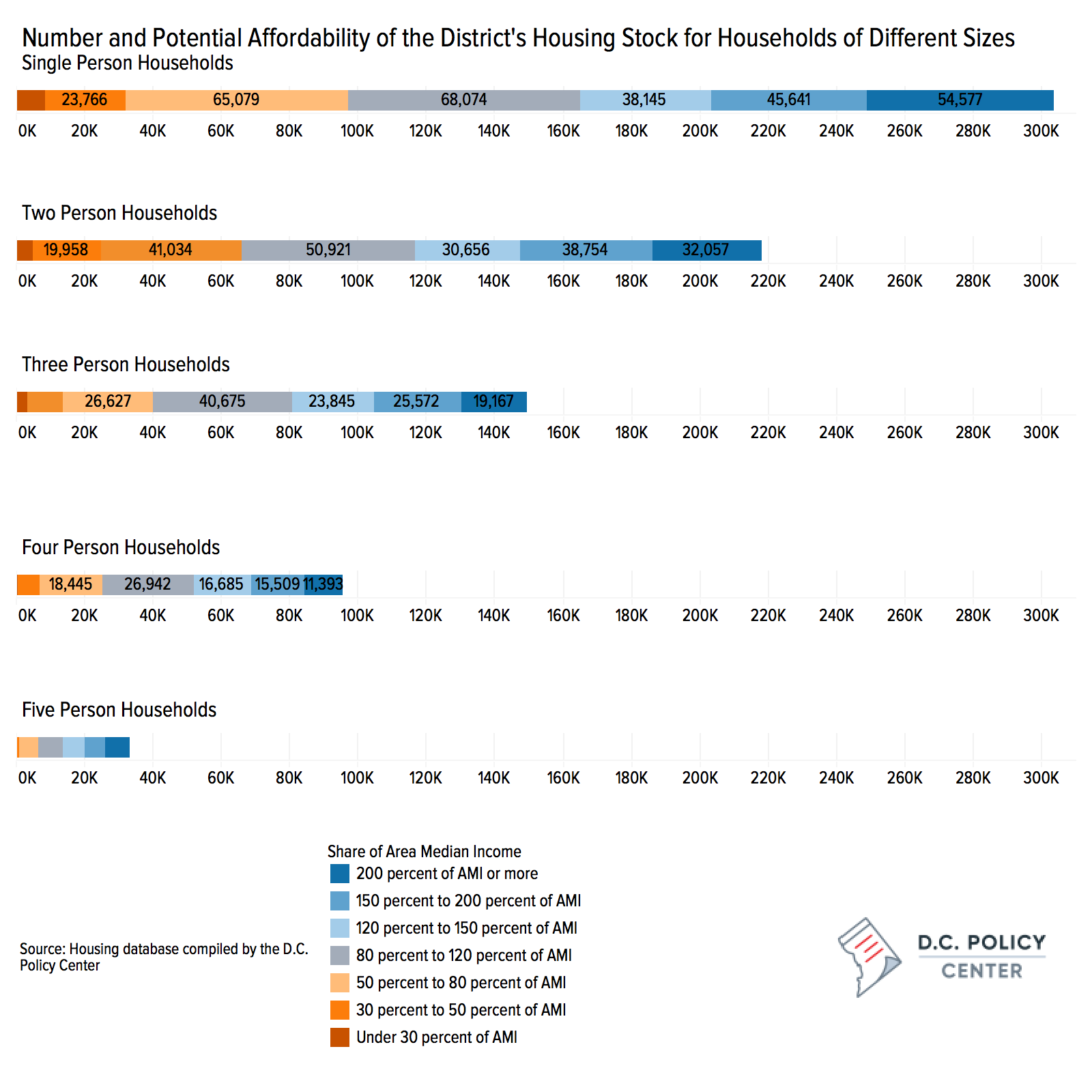

Many of the family-sized units are potentially affordable for smaller households.

Single person households can potentially live in all units—from tiny studios to large mansions—so long as they can afford them. Based on the values we estimate from tax assessments, we find 97,064 units potentially affordable for singles who earn under 80 percent of Area Median Income —the cut-off level for all of the District’s affordable housing programs. There are about 68,000 units that middle-income singles can potentially afford. Many of these units—17,860 to be precise—are large enough to accommodate families of four or more. And about 45 percent of the District’s housing stock is ostensibly too expensive for singles, but as we will show later, there are many affluent singles in the District that can compete for these units.

See an interactive graph with full data here.

For two-person households, 218,200 out of the 303,910 housing units in the District’s housing stock are suitable (excluding very small units and studios). There are 65,870 units that could be affordable to those who earn 80 percent of Area Median Income or less (21 percent of the entire housing stock). A quarter of the housing stock that can hold two persons comfortably (50,900 units, or 17 percent of the entire housing stock, regardless of size) are potentially affordable for middle-income couples earning between 80 percent and 120 percent of Area Median Income I. For a family of three, slightly under 40,000 out of 149,300 units (13.2 percent of all housing stock) are potentially affordable at 80 percent of Area Median Income or less and 40,700 units can be afforded by middle-income households. There are about 95,170 units that can comfortably accommodate four or more persons, and out of these, only about 25,100 (8.2 percent of all housing stock) are potentially affordable for a family earning 80 percent of Area Median Income or less. A family with three children must pick from a shallow pool of 32,930 units and if they earn less than 80 percent of Area Median Income, their choices are limited to 13,700 units (less than 5 percent of the entire housing stock in the District).

There are too few small units relative to the number of small households.

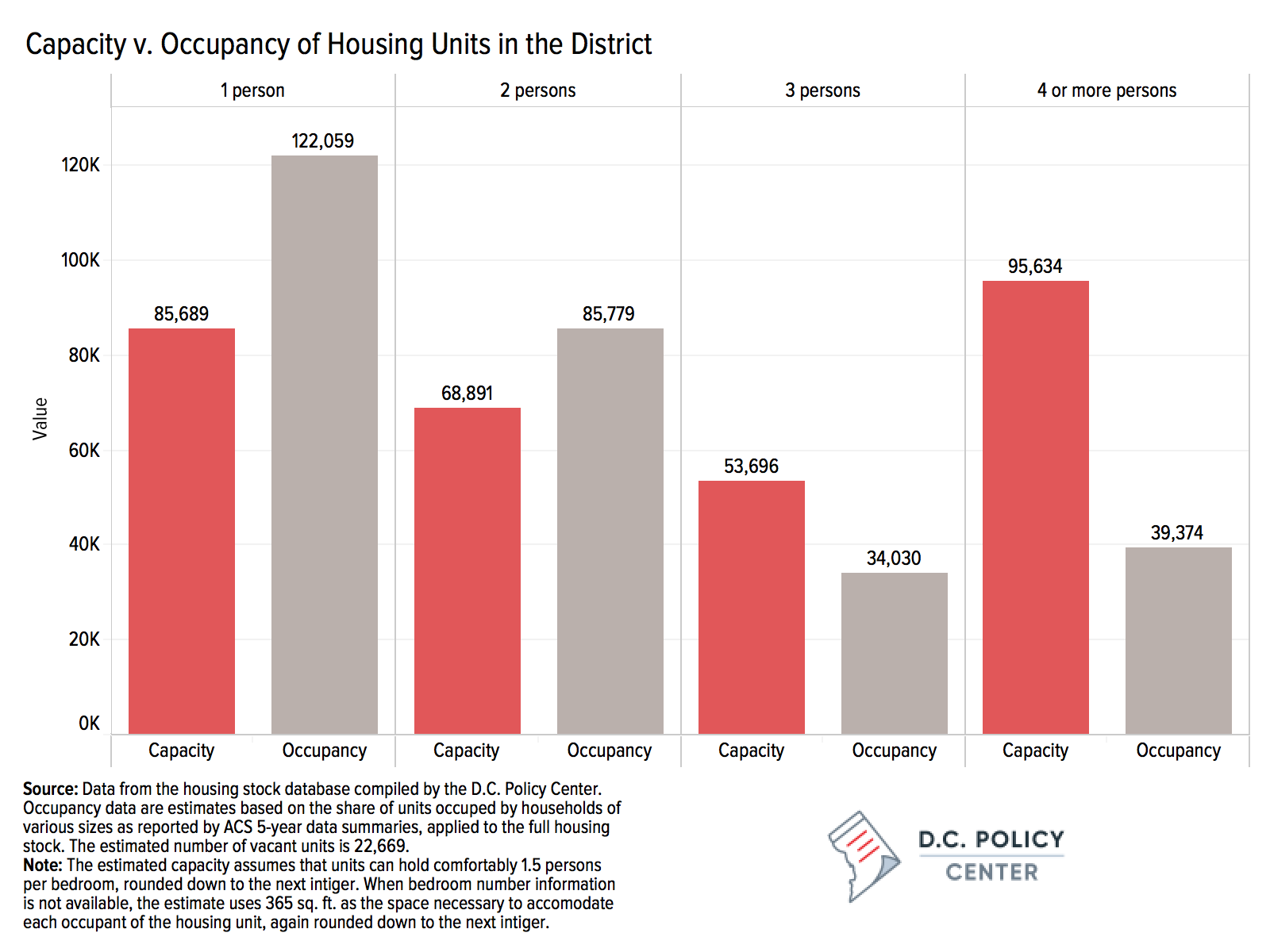

We estimate that about 51 percent of the District’s housing stock (154,500 units) can comfortably accommodate only one or two persons. Another 18 percent (53,700) can comfortably hold three persons, such as a new family with a single child and only 14,600 of these units are single family homes. The rest are condominiums and rental apartments, with just a couple thousand cooperatives added to the mix. 31 percent of the housing stock (95,600 housing units) can accommodate a family of four, and 82 percent of these are single family units, and only 8 percent (7,216 units) are large rental apartments.

The comparison of the estimated capacity of the units to their occupancy shows a great discrepancy between household structure and the housing inventory in the District. The estimated number of units that can comfortably accommodate one or two persons is 154,600. However, the estimated number of housing units with one or two occupants, based on our estimates using national survey data, is 207,800. There is enough housing stock to accommodate households of three persons (53,700 units compared to 34,000 units with three persons actually occupying the unit). Same is true for larger households of four and more persons (95,600 units compared to 39,350 such households). The data show that singles and couples—some of them seniors—are occupying larger units, and their demand (especially demand from the more affluent ones) is increasing the cost of housing for families.

This discrepancy between capacity and occupancy has important implications on how we think about affordability. First, it tells us that market rate units of all sizes, including small units, to the extent that they can satisfy the demand from smaller households, can help preserve affordability and reduce displacement. An influx of small units alone would not necessarily remove all the competitive pressures. Smaller households do value space and many of them can often pay for it. But smaller units in neighborhoods favored by singles, young couples, or even empty-nesters could help. Second, it shows that families are competing with singles and couples for family-sized housing. Given the high concentration of small and affluent households in the District, this competition and the subsequent increase in prices push low and middle-income families out of the District, particularly when we consider the affordability of units.

Middle-income families face competition from affluent singles and couples.

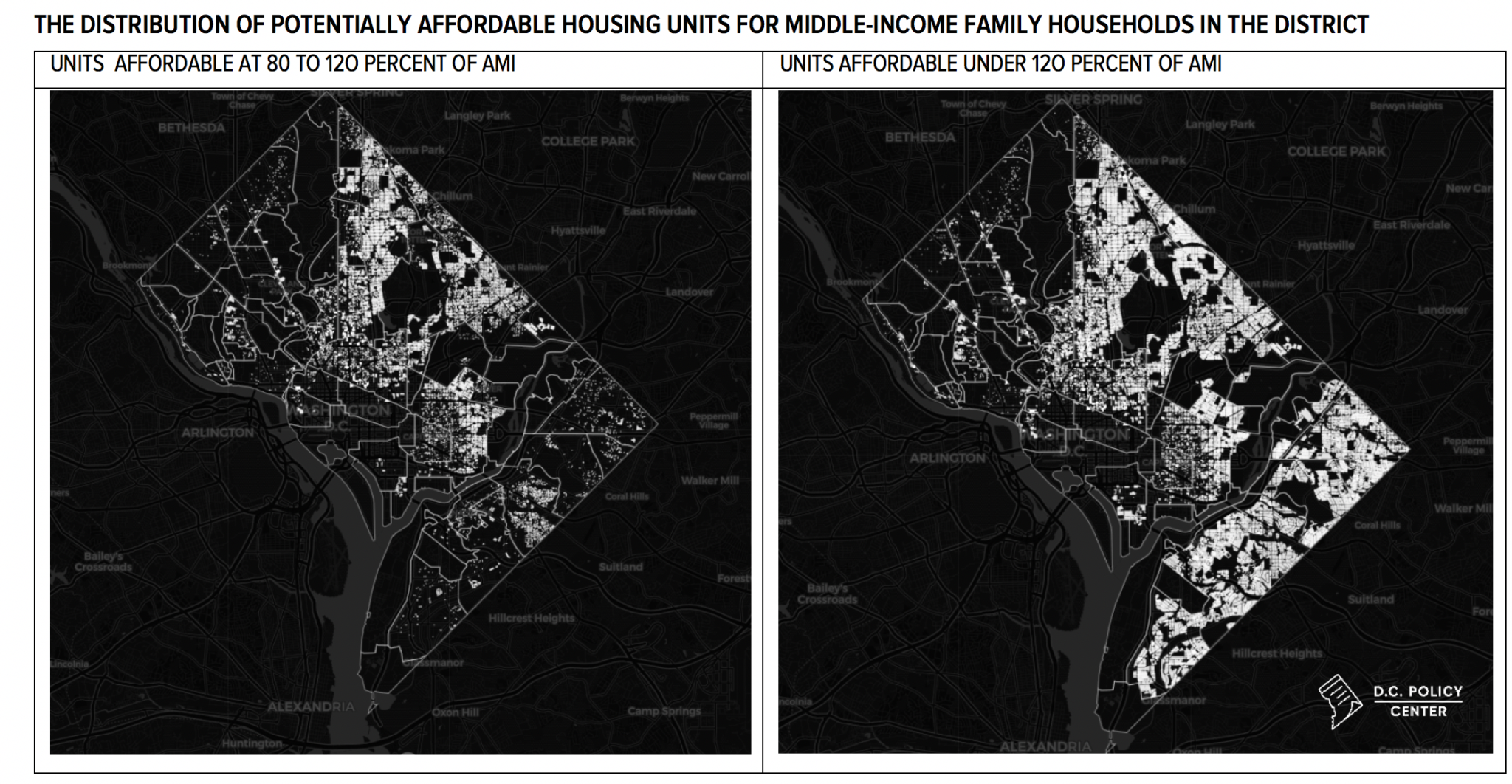

The District’s housing stock has 26,900 units large enough to hold a family of four that are potentially affordable to middle income families who earn 80 to 120 percent of Area Median Income. If we include in this count units affordable below 80 percent of Area Median Income, the number swells to 52,000. For those looking for a neighborhood where most housing units are middle-income (affordable at 80 percent to 120 percent of AMI), the choices are limited to a handful of neighborhoods east of 16th Street and west of the Anacostia River, beginning at the District’s northeast border down to Massachusetts Avenue, and following the question-mark shaped Central City tax assessment neighborhood. If we expand the neighborhoods to include all housing units potentially affordable at or below 120 percent of income, we see a pronounced shift to east of the river communities.

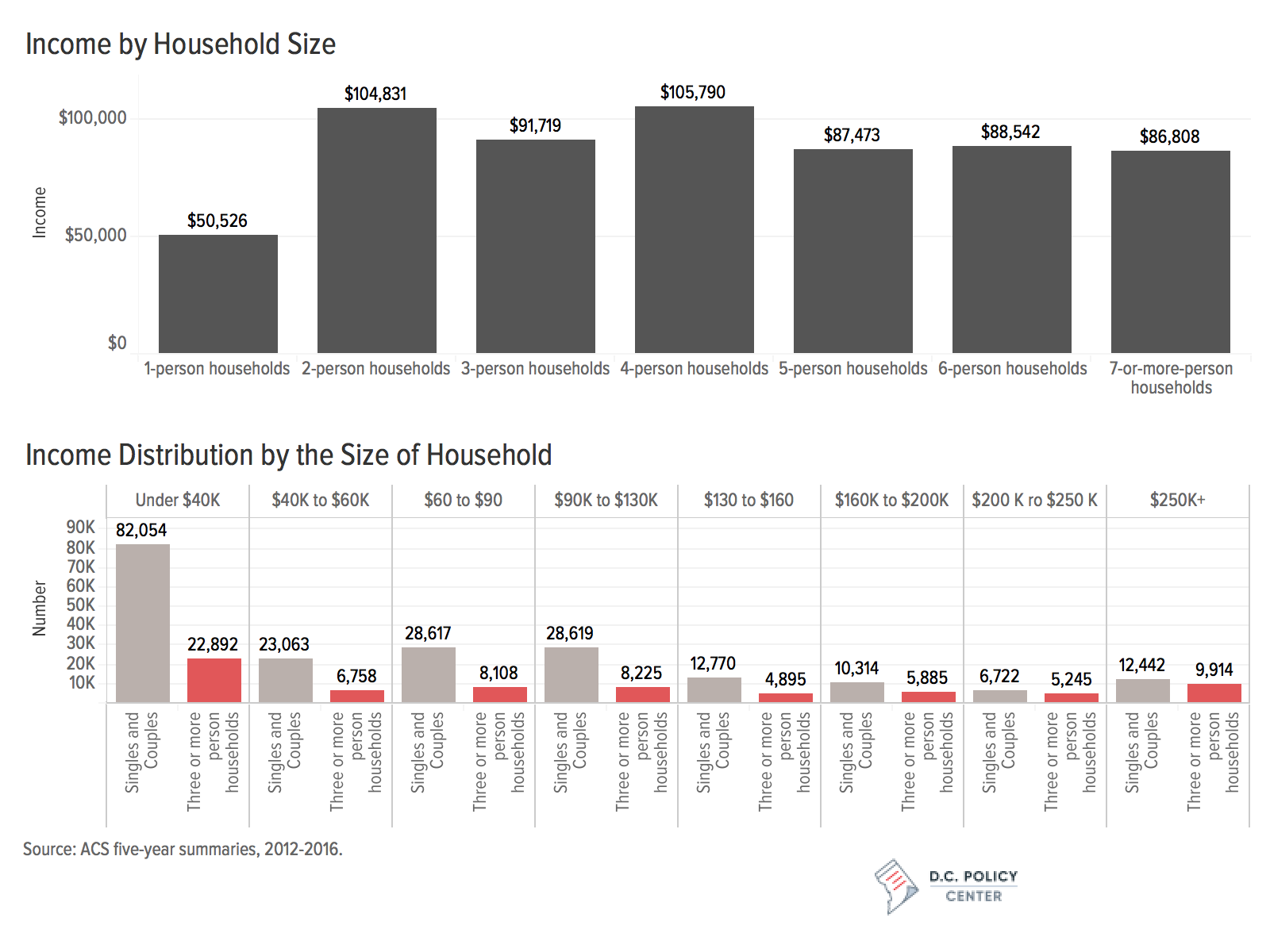

The District has a lot of affluent singles and couples who compete for housing units. The median income of households with two persons in the past 12-months (adjusted for inflation) was $104,831. This is equivalent to the median income among households with four persons, and higher than the median incomes for households with five or more persons. Furthermore, at every income level, there are more single and two-person households compared to households with three or more people. This is purely a function of the city’s demographics. For example, among those who earn between $90,000 to $130,000—the band of area middle income for families—the number of single and two-person households outsize households of three or more persons by over 20,000. These smaller households, especially if they do not have to incur the expenses related to having children, can spend a larger part of their incomes on housing, and put pressure on prices.

Even among the higher-valued units, competition from smaller households could be formidable. We estimate that of the 26,900 family-sized units in the District’s housing stock that are potentially affordable to middle-income households with four persons, 9,000 could also be viable options for singles who earn 150 percent of Area Median Income or more. There are 30,300 single-person households with such income in the District. Furthermore, 14,161 are potentially affordable to couples that more than 150 percent of Area Median Income. And there are 32,200 single-person households with such income in the District.

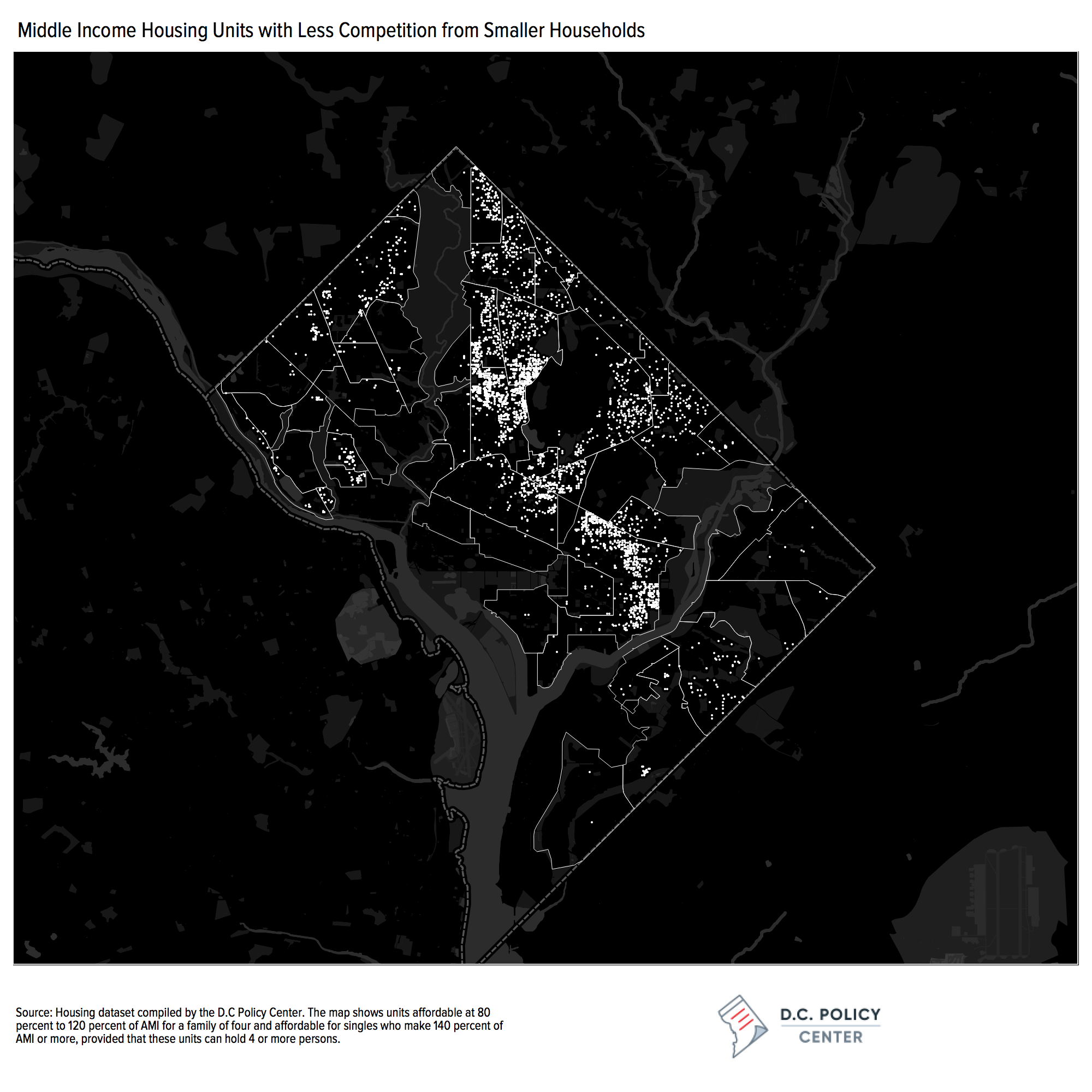

The map of middle-income units that face the least competition from affluent couples and singles explains why families live where they live in the city. Once we remove from the map units affordable for couples who earn 140 percent of Area Median Income or more for a two-person household, we are left with the neighborhoods to which families have been gravitating. We see heavy concentrations of units in Shepherd Park north of Walter Reed, Brightwood, Petworth, north of Colombia Road in Colombia Heights, in Kingman Park and Hill East. This is not to say that finding middle-income family housing in these neighborhoods is easy, but it is far easier if a family limits its search to neighborhoods where there is less competition from singles and couples.

The least and most affordable family-sized units in the District are far from each other.

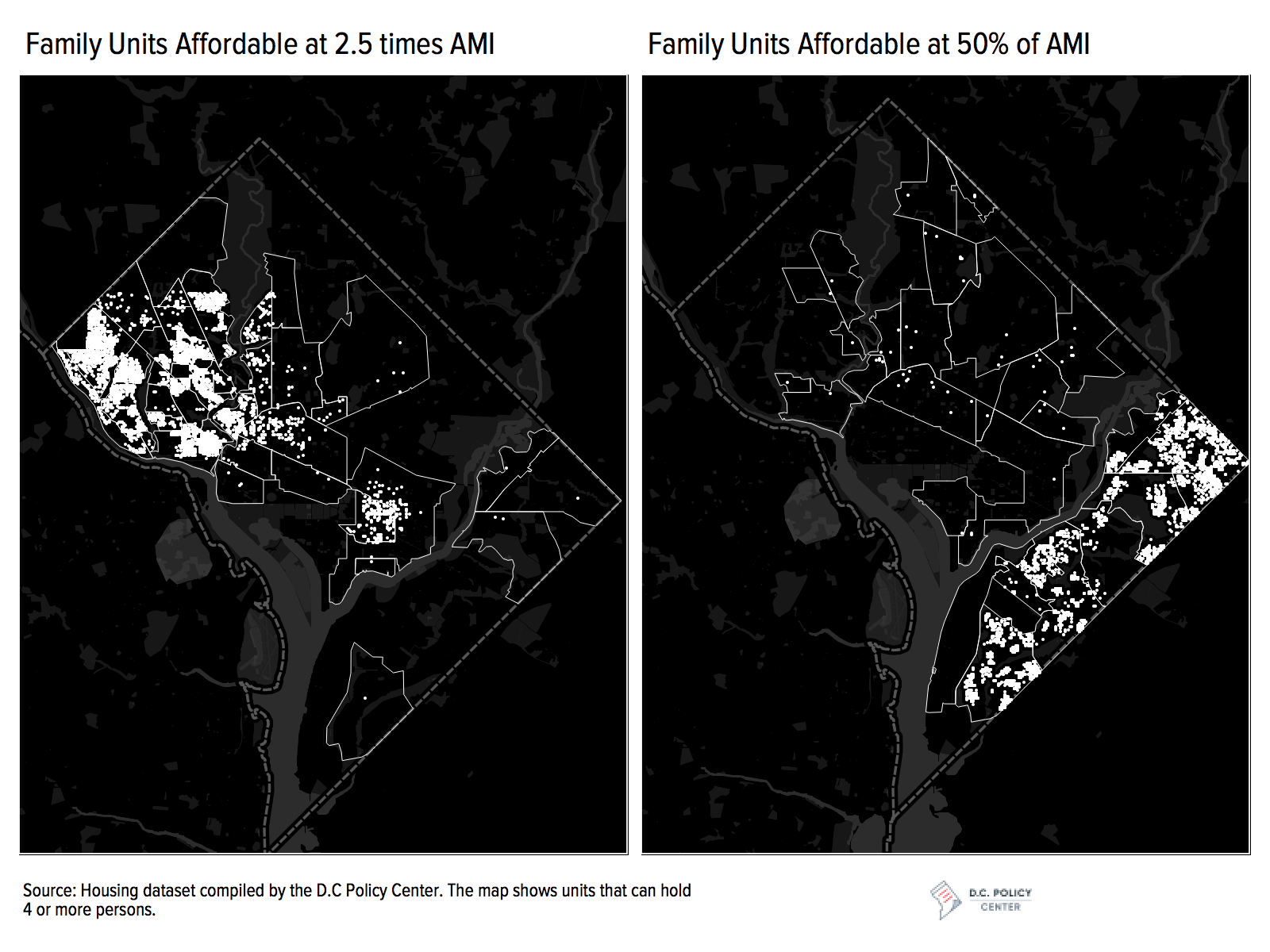

The geographic distribution of the most and the least affordable housing units in the District highlights the deepening economic segregation in the city. Based on our methodology, we have found about 4,800 units which require an annual income of $276,000 or more—which is 2.5 times the Area Median Income. This is 1.6 percent of the entire housing stock in the District. Except for Capitol Hill, these houses are concentrated west of the Park, and especially south of Massachusetts Avenue, and located nowhere near the most affordable homes (we count 4,600 units affordable at 50 percent of Area Median Income, or the equivalent of annual income of $55,000).

Virtually all units most affordable for low-income families are east of the Anacostia River. The following is a point often made but is worth repeating: High and low-income residents in the city live far away from each other. Residents in these disparate neighborhoods share very little in their day-to-day lives: Not the schools, the bus lines, or the libraries; not the restaurants, the supermarkets, or the gas stations. This, combined with the extreme income inequality between black and white residents in D.C., further compounds the city’s segregation by race, and continues racial inequities.

The District needs more units and better land use.

The analysis presented in our report has four key findings. First, competition from affluent singles and couples is an important but often overlooked factor in the undersupply of affordable housing for low and middle-income families. Second, restrictive land use policies also play a role, as they have produced a housing stock largely composed of single family homes, especially in neighborhoods with public and private amenities such as good schools, safe public spaces, and proximity to transportation and quality retail. Third, lack of public investments in many communities in the east of the river is ill-serving the current residents who live there and even though these communities have affordable homes, they do not provide the amenities families are looking for. And finally, these housing and land use policies, combined with disparate amenities across communities, have created an extremely segregated housing market, where the lowest and highest valued homes are completely separated, and the residents of these homes live lives apart.

Two important implications follow: First, any unit that comes on the market that can satisfy the demand from affluent singles and couples can have a significant impact on the availability and affordability of housing for all. Studies elsewhere have shown that communities with the greatest expansion of market-rate housing also see the least low-income displacement, and market rate housing can make a significant impact in preserving affordability. Our study suggests that these forces are also very strong in the District of Columbia.

Second, in a land-constrained city like the District of Columbia, the city should focus on making the most out of its undeveloped and underdeveloped land. Some neighborhoods in the northeast and southeast quadrants of the city have significant housing stock that is affordable to families but lack the resources that these families would need to truly thrive. Lack of public and private investments in amenities desired by families such as good schools, safe streets, access to transportation, quality retail, and employment centers ill-serves the low-income District residents who live in these neighborhoods, reducing their quality of life and limiting their livelihoods and opportunities for their children. These exacerbate the racial and socioeconomic divides in our city. On the other hand, some neighborhoods in the Northwest quadrant of the city have tremendous amenities but lack the mix of housing that would make these neighborhoods inclusive and accessible to a wider range of incomes. Restrictive land use and zoning regulations have placed these neighborhoods beyond the reach of low and middle-income families. These discrepancies between land use and demand are as detrimental exclusion factors. Taken together, investments in the form of better amenities in some neighborhoods and more flexibility under zoning laws for increased development in others will make a meaningful difference in the availability of housing for low and middle-income families.

To be sure, many residents fear such changes. Some worry that once their neighborhood becomes more desirable, gentrification will displace the lower-income residents who currently live there. They worry that the units that now serve the very-low income households will disappear, pushing these residents out of the city. Others, who want to preserve the look and feel of their neighborhoods, worry that increased density and new development will dilute the housing values. Understanding where our housing stock falls short of meeting the demand is important in shifting the conversation to finding ways to increase access, affordability, and inclusivity, and ease these fears.

Market forces—supply and demand—have produced the current stock, but government policies and historical context matters too.

Much of the housing that exists is because developers bought the land and built the housing they thought they could sell or rent. The forces of supply and demand determine the stock and its prices and rents within the current regulatory framework. That smaller households occupy larger units is not necessarily a mismatch, but more a realization of what people want, and what they can pay for. Preferences of the residents play a big role: Smaller households are attracted to larger units because they value the additional space or the neighborhoods where these homes are located. For many, the District’s single-family neighborhoods are convenient, close to amenities, and therefore attractive. And the District attracts affluent singles and couples who can pay for these units. For seniors, staying in their current, large house is sometimes the only feasible option. These forces will not change quickly, and certainly not in the absence of alternatives that can meet the demands or needs of smaller households.

The District’s history, especially in the context of national housing policies, also contributed to the characteristics of the current stock and the distribution of the city’s residents across the current stock. The Northeast and Southeast quadrants of the city are mostly black and low-income in part owing to federal and District housing policies. As Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove describe in Chocolate City, urban renewal wiped out all of Southwest’s buildings, forced out fifteen thousand businesses, and displaced twenty-three thousand residents (70 percent of who were black and 90 percent poor), and the 5,800 new units built here were too few and too expensive for Southwest’s original residents. As a result, most inhabitants of these Southwest neighborhoods moved elsewhere in the city. Almost half (46.5 percent) moved to the Southeast quadrant of the city, were zoning changes that began in the 1950s had reserved 75 percent of residential land in the furthest corners of the quadrant for rental apartment buildings. Another quarter of those displaced by urban renewal moved to the Northeast quadrant, which included many single-family homes, but public and private policies presented barriers here as well. Federal housing programs from 1950s such as FHA and VA loans and the GI Bill were closed to black residents; restrictive covenants, though legally unenforceable since 1947, were well-alive in practice, which led to black residents paying twice as much for housing compared to white residents and living in units that were five times more crowded. The lack of representative government made the problem worse. Black residents were not represented on the city’s boards or commissions and received no hearing from the federal government, which often acted against District residents’ best interests.

The District, like many other cities, has adopted an array of policies to encourage housing production, preserve neighborhoods, and deal with affordability issues. These policies include building codes for safety, taxation to raise money for services, zoning to preserve neighborhood character, and much later, anti-discrimination laws. To deal with affordability, there is rent control, public housing, participation in federal programs (such as FHA loans and Section 8 rental assistance), the Housing Production Trust Fund, DOPA and TOPA laws, Inclusionary Zoning, and preservation efforts. There is the homeowner and elderly exemptions from property taxes, a “circuit breaker” program that allows low-income taxpayers to deduct from their income taxes part of their housing costs, and tax deferral for seniors who are struggling to pay property taxes. Particularly around Metro stops, the city has encouraged mixed used developments with larger apartment houses, mostly with small units. That these policies have been adopted does not mean they been successful in accomplishing their stated objectives or are free of unintended consequences.

There are no easy solutions, but policies that reconcile the supply and demand in the market economy with affordability will help.

Many factors need to come together to create policies that can produce or enable market forces to produce affordable, desirable housing with access to public and private amenities. The analysis presented in our report suggests that constructing more housing, especially housing that would be appealing to affluent singles and couples or seniors, is necessary to relieve some of the pressures on the housing market. It also suggests rethinking how we repurpose the existing stock and use the District’s land and public resources to create more inclusive communities with investments in neighborhoods to build better schools, better transportation networks that meet the needs of the residents, and achieve higher density to create a better business climate that can attract businesses and amenities to all parts of the city.

One important factor in reconciling the desire to have affordability with market forces is to consider what the city will look like in the future under current policies (given projections about population growth and economic conditions) and whether that future is a desirable one. One study estimates that the District will have to add over 105,000 units over a thirty-year period (beginning in 2012) to meet the demand of its growing population.[6] That is an estimated 5,262 units each year. [6] To the extent that the District will remain attractive to newcomers, without concurrent adequate growth in housing units, more residents will be displaced from their neighborhoods and more future residents will be excluded. Furthermore, these forces will play out in the context of the entire metro region, pushing young families or low-income residents to the outer suburbs of the metropolitan area where housing remains more affordable. Such trends will force the District’s workforce further away, increasing the time and money costs of commuting. And increasing housing costs will exhaust the economic wealth the District creates at the expense of growth.[7]

Another factor is what an inclusive city could (or should look) like and how market forces and government programs can be combined to help the city get there. Inclusivity could mean many things: mixing incomes, mixing households of all sizes, or having residents of all ages and all races and ethnicities, or a combination of these. But beyond that, the term remains underdefined because it is extremely hard to build an infallible vision around a more granular or neighborhood-level view of inclusivity. The District has a long history of segregated neighborhoods, by both income and race, and recent demographic and economic growth has not reversed this type of segregation. In fact, concentrated poverty and segregation has increased. The city’s housing policies—both historical and current—have contributed to this outcome. For example, the District’s subsidized housing tends to congregate in lower income neighborhoods[8] because of high land costs or unavailability of buildable land elsewhere. Investments in public transit and transit corridors are uneven across the city, and sometimes not accompanied by sufficient increases in density to support growing demand, creating islands of gentrification. Market forces that would increase the mix of incomes and household types would have to rely on the ability to build such mixed-income housing through more permissive land use and the making of inclusivity a higher priority in new development. So far, the new neighborhoods in the District are not necessarily mixed: NoMa, which developed after 2000 is rather uniform in the type of housing it offers and the income necessary to live there. Large-scale redevelopments such as the former Walter Reed Hospital site, Saint Elizabeth’s East Campus, and part of the McMillan Reservoir site include significant mix-use and affordable housing components. Other potential redevelopment efforts on unbuilt land—such as the RFK stadium site, Old Soldiers’ Home, or Poplar Point can dramatically boost housing, but sometimes federal restrictions on land use, as in the case of RFK stadium, make this extremely difficult.

Related to inclusiveness is the regional view, an important but often-ignored factor in housing. The District holds 10 percent of the population of the larger metropolitan area, which is the true economic unit with a single labor market, a single workforce, and an intertwined customer base, including for housing. Residents continuously weigh housing options across the entire metropolitan area, trading longer commutes for more expensive housing, which result in shifting demographic patterns. Therefore, housing policies adopted by the different jurisdictions in the metropolitan area shape a single housing market. But despite this interdependency, and the presence of several organizations that bring people together to discuss regional issues, there is little collaboration across the jurisdictions—even though jurisdictions across the region have deployed tools very similar to the ones the District has adopted to increase affordable units. In this fragmented policy environment, the supply of different types of housing shift to where it is financially feasible to build, sometimes pushing workforce too far away from employment centers. For example, new housing construction is no longer concentrated in the inner suburbs such as Fairfax, Montgomery, and Prince George’s Counties, but has shifted either to distant suburbs, which has become the destination for young families, or the inner core, which has become the destination of singles.

Employer engagement in housing issues in the District of Columbia is limited but can play a large role in coordinating regional efforts. Workforce housing—housing for middle-income families who are not otherwise eligible for government support or subsidies[9]—is a real concern as many middle-income workers, like restaurant staff, healthcare employees or bus drivers, are often those who cannot telecommute, are thus pushed further away from the District, and their long and unpredictable commutes are potentially damaging to their places of employment. Yet, interest and employer engagement in the production of workforce housing is limited. Through stakeholder interviews, Pamela M. Blumenthal et al. (2017) link the lack of employer interest and leadership in workforce housing to the dominance of the federal government in the region that limits the impact of the private sector. Plus, many large employers such as defense contractors, hospitals, and hotels, have multiple small campuses, and therefore take advantage of the regional distribution of the workforce. In the District, the continuous influx of young, skilled workers who can live in nearby smaller units alleviates the workforce pressures for most professional and management firms.

A preference shift to smaller housing units accompanied by policies that allow urban fill can also help. We show in this study that the occupation of larger units by smaller households—couples, singles, and sometimes seniors—is a major pressure point on the District’s housing market. The city has taken an important step in allowing the development of Auxiliary Dwelling Units to enable urban fill, especially when moving houses or downsizing is financially difficult or would separate the residents from their communities. But, the current composition of the housing stock partly reflects the demand for more space—a backyard, an extra room for guests, an office or room for hobbies, or a basement for storage. The desire for space will always work against allowable density increases, regardless of the regulatory regime. For cities to take advantage of their potential density, at least some of the residents must develop a preference for living in smaller spaces—not just microunits for couples or singles, but also the types of units in which families live in high-density cities elsewhere, such as two or three-bedroom flats in multifamily buildings. Some neighborhoods fear density because of the potential traffic congestion, higher incidence of crime, and other factors. They worry that increasing density will change the neighborhood characteristics. But higher density cities are more efficient, with greater public transportation use, shorter journeys, and smaller carbon footprints. Density also fosters economic activity such as restaurants, grocery stores, and other businesses are attracted to places with many people. Additionally, density does not always imply height: population density in Paris—a uniformly low-rise city—is 55,673 persons per square mile, which is nearly five times the District (11,367 persons per square mile). Educating residents on the benefits of density can allow the city to make most of is scarce land.

The findings of our study highlight the need for a shift in thinking in how residents envision the future of the District of Columbia and their neighborhoods. Constraining new residential development or having it take place in only a few designated areas of the city will exclude low and middle-income families from the District. A more inclusive city must have more mixing of incomes and household types across its neighborhoods, and less of a divide between where its rich and poor residents live. But this is only possible by building more housing. Our study suggests that relieving zoning restrictions in parts of the city with amenities desired by families, while using city resources to improve the public amenities in others to make the current stock more attractive is crucial. But these changes must also harness other forces that change the supply and demand patterns: a more regional focus, more engagement from employers, and an increasing preference for denser neighborhoods.

Click here to read the full report.

About the data

The analysis presented in this study relies on estimates of housing units and housing values built from a comprehensive dataset that combines information from eight publicly available sets of data:

- Real property tax assessment database which provides information on the use of each property, the assessed value of each property, the type of tax classification for each property and whether the property is exempt from taxation or receives special tax treatment.

- Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal data for residential units, which provide information on the characteristics of the residential units, including living area, characteristics of the structure, and age of the structure.

- Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal data for condominiums, which provide similar information for individual condominium units.

- Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal data for commercial property, which provide information on apartment buildings that are assessed as a single entity. Not all these buildings are commercial, in the sense that they have units available for rent. They also include cooperatives where a single corporate entity owns the buildings of the cooperative and is responsible for the real property taxes.

- Common ownership lots spatial dataset, which is a map of all lots in the District of Columbia.

- A spatial dataset called the “Condominium relate file,” which maps all condominium units that are assessed separately to a single common ownership lot on which the condominium building resides.

- Assessment to sales price report for residential properties published by the OCFO

- Capitalization rates used in real property assessment, published by the OCFO.

Full description of the methodology used to estimate the number, capacity, and valuations of units can be found at the Appendix section of the full report here.