January 1, 2018 was the day the District fully implemented its tax reform that began in 2015. January 1 was also the day of its undoing.

January 1, 2018 was the day the District fully implemented its tax reform that began in 2015. The Federal Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2018, which took effect on the very same day, redefined what is taxable income in the District. In doing so, it did away with $93 million of personal income tax reductions that was a part of the Tax Revision Commission’s attempt to reduce personal income tax burdens, and replaced it with disproportionate increases on the effective rates on low and middle income residents (why, net impact, effective income tax rate changes by income groups).

But, by then, the interest in tax reform had waned. The money came at an opportune time, so it was spent.

To be sure, the District is, in one very important way, much more committed to sound tax policy than many other states and localities. There have already been two Tax Revision Commissions since the Revitalization Act (one in 1998, another one in 2012), and both produced reform packages that guard sound tax policy principles: creating a simple, efficient tax system that maintains competitiveness by imposing as little disincentives as possible on economic activity while reducing tax burdens on low income residents. The District adopted both packages with small modifications.

The 2014 Tax Reform Package was especially celebrated for its ability to balance competitiveness, simplification, and progressivity. An unusually large and diverse collection of entities from the left, the right, and the center approved. The Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, Citizens for Tax Justice, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Vox.com, the National Taxpayers Union, the Cato Institute, and even Grover Nordquist’s Americans for Tax Reform all chimed in with supportive commentary.

But inbetween, sound tax principles are forgotten. Especially when under pressure, the District’s tax policy collapses into an exercise in getting to a number to plug into the budget, with no demonstrated consideration for what will keep its tax regime simple, and little for maintaining a fair and competitive tax system.

Granted, economists and policy analysts do not have to worry about political or time pressures when we are formulating, analyzing, or criticizing tax policy. Tax revision commissions need to build consensus, but not in a political environment. And this consensus has been a strong enough political pressure on District policymakers to deliver adoption. In contrast, the budget is highly political and formulated in an environment that does not always award good tax policy. Still how much we have moved from first principles in the short time span since January 1st is worth a review.

Metro funding is a combination of implicit income tax increases, sales tax hikes, and property tax restructuring.

Metro funding was the critical priority in this year’s budget. The soundest policy for paying for Metro is a regional tax that can tap into the regional benefits the public transportation system creates. A regional sales tax is particularly suitable because it taxes the economic activity supported by the Metro system. A regional tax on real property, which capitalizes on much of Metro’s value, makes similar sense. But despite good efforts, the interjurisdictional politics did not allow for the adoption of a regional tax. So, the District had to come up with its own funding plan.

The budget proposal shows that the District has committed its sales tax revenues to fund its additional Metro obligations. But that is not how the city is paying for this obligation.[1] Sales taxes go up, but gross receipt tax hikes on ride shares, commercial real property tax increases, and the “windfall” from the federal tax reform fill the rest of the gap.

With the proposed budget, the city will be taxing the same value at two different rates.

The property tax proposals, when listed together, present a set of bewilderingly disconnected, and sometimes conflicting and counterproductive policy choices.

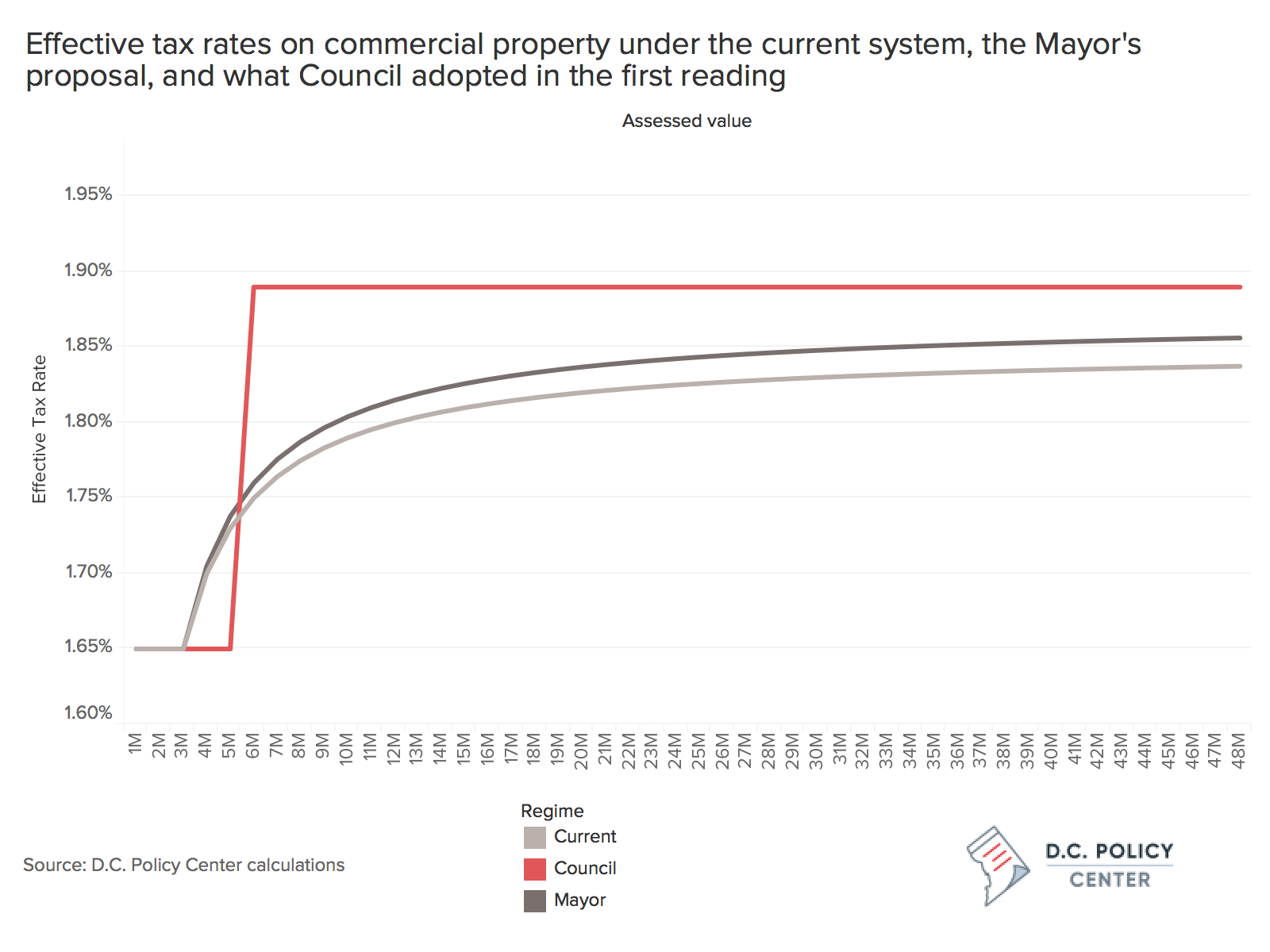

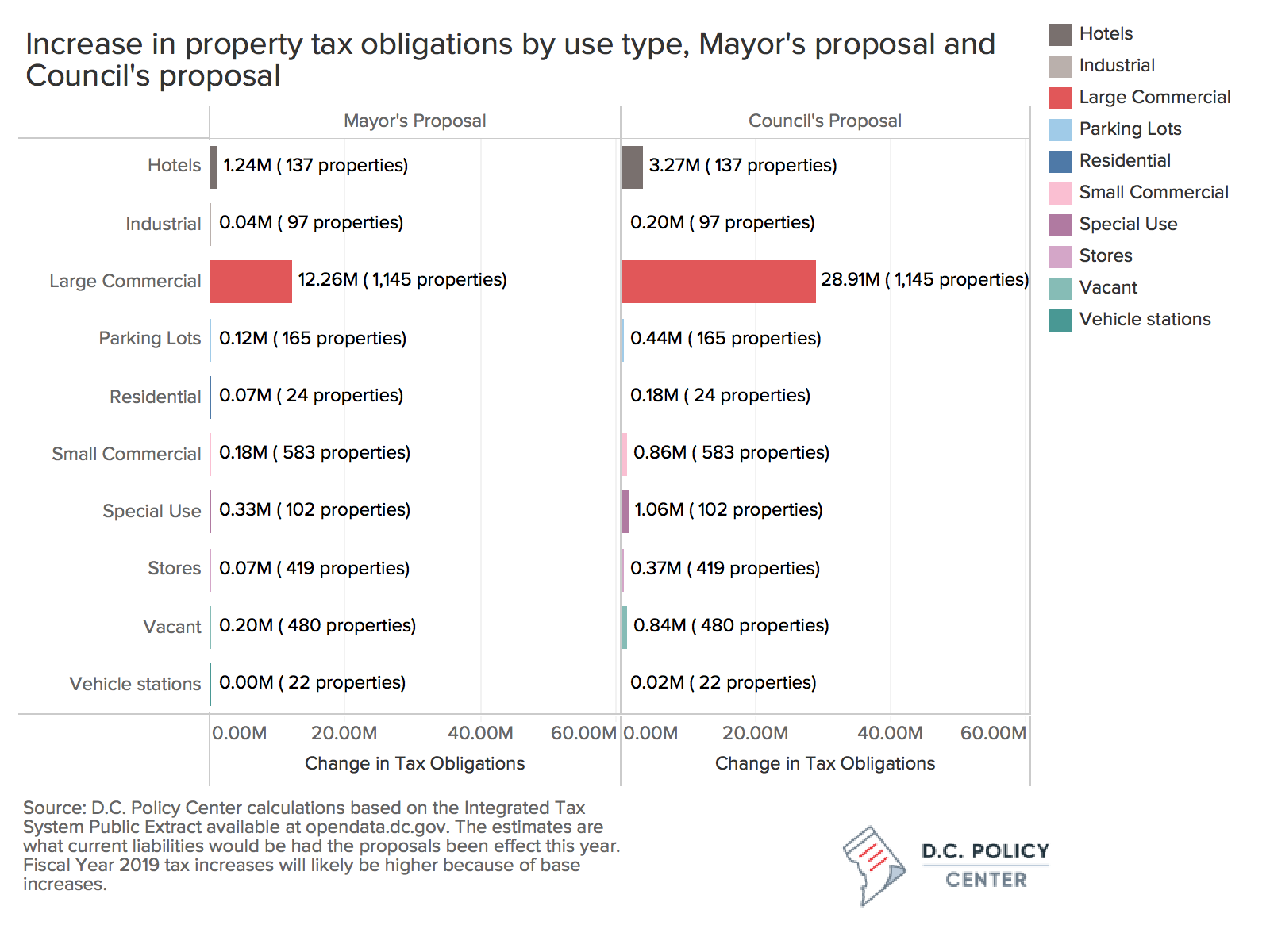

First is the change to commercial real property tax structure. The District has two different tax rates for commercial real property. The city taxes the first $3 million in assessed value at 1.65 percent and any value above that at 1.85 percent. The mayor proposed to increase the higher tier tax rate to $1.87 percent, generating an additional $16.7 million from larger buildings or properties in prime locations. The Council is proposing a major change to the system creating two different tax rates based on value—a particularly worrisome choice—that will generate, in my estimation, another $25 million.

Compare the effective tax rates under the current system with what the mayor proposed and what the Council adopted in the first reading. Under the current system, the effective rate is 1.65 percent for values up to $3 million and increases gradually as assessments grow but never quite reaches the top rate of 1.85 percent because the first $3 million in assessments are always taxed at 1.65 percent. While this model penalizes large buildings that efficiently pack many tenants and employees—a valuable feature to be supported in a land-constrained city like the District—we have come to accept it as a “commuter tax” as many of the tenants in these buildings (and their employers and customers) are non-residents. The Mayor’s proposal preserves the same structure but increases the pace of growth in the effective tax rate.

The Council proposal increases the effective tax rate by 24 basis points (from 1.65 percent to 1.89 percent) for properties valued just over $5 million (and giving a tax cut of at most 8 basis points for properties under $5 million). This is worrisome for three reasons.

First, the new structure awards low valuation. Time will show if this is large enough an incentive to slow down redevelopment of small properties. But whatever the effect is, it will have a greater impact in parts of the city where values are low because economic activity is not particularly strong, especially in Wards 7 and 8 where redevelopment and economic activity is sorely missing and urgently needed. The Council concedes this point in the very same budget by providing tax incentives for grocery stores and other development in these wards.

Second, because the property tax threshold ($3 million under the current regime, $5 million under the Council proposal) is not indexed to price level increases or growth in property valuations, every year a new set of properties will graduate into a higher tax bracket. This is a problem now but will become a much bigger problem under the Council proposal. To wit, I found 63 properties that were assessed under $5 million in Tax Year 2017, and over $5 million in Tax Year 2018. Some of these are significant redevelopments, but over half appear to be assessment increases due to annual value growth, which is about 3.3 percent in the District. Owners of these properties saw their taxes go up by an average of $2,700 this year, but under the proposed regime, the same tax bills would have gone up, on average, by $38,000. May be 30 to 40 properties in a single year is a small number among the 3,200 commercial property taxpayers. But over ten years, over 10 percent of taxpayers (and their tenants, as explained next) would experience this tax shock.

Importantly, the proposal will not capture increases in land value due to public investments, an idea with historical economic underpinnings that is generating much recent interest (here, here, and here). Taxing real property is an attractive means of collecting local tax revenue because the government can extract the value of public investments that capitalize in land values and use this to pay for current spending and investments. But under the current design, the real world interferes with its commercial lease practices: Much of the office space in DC is leased through arrangements that allow property owners to pass any increase in the costs of operating a building, including the real property taxes, to their tenants. So, when taxes go up, tenants pay. These tenants might not be able to get out of their leases right away, but will consider a move elsewhere as soon as they can (as AIR, and the Grocery Manufacturers Association did) or will demand other government interventions to stay in the city (here).

Some proposals offset each other, causing little net change in the immediate burdens but different impacts in the future.

The Council’s proposed property tax changes also interact with its own changes to the sales tax portion of the Metro funding. In one case, the net effect is almost zero.

The mayor’s proposal included a 0.25 percentage point increase in all sales tax classes including general sales tax, taxes on restaurants, and taxes on hotels. The Council proposal eliminates the increase on restaurants and reduces the increase in hotel taxes to 15 basis points. My best estimate is that the 10-basis point reduction to the mayor’s proposed will reduce revenue hotel sales would have contributed to Metro funding by about $2.2 million.

The sales tax cut for hotels (from the mayor’s proposal) is almost exactly offset by the new property tax structure. I found 137 properties classified as hotels, motels, or inns in the District’s real property tax database. Their property taxes will collectively go up by $2 million under the new property tax regime. Perhaps the implicit reasoning is because hotel guests will not see a higher tax on their bills, they will be less inclined to get a room in Arlington or at the National Harbor. But higher taxes on the buildings will dampen efforts to invest in and maintain hotel buildings in the long run.

While increasing commercial real property taxes, the budget also offers targeted tax benefits for small businesses that cannot generate sufficient income to pay for their costs.

The Council is also proposing a “circuit-breaker” type program to benefit small retailers with gross receipts under $2.5 million. These establishments will be eligible for a business tax reduction for up to 10 percent of their rent or property tax obligations, capped at $5,000. The proposal is modeled after the popular Schedule H program for low income households in the District. The credit is refundable, so even entities that pay less than $5,000 in franchise taxes will receive it. The Council documents note that 4,400 establishments could benefit from this subsidy.

For establishments that qualify, this credit will certainly help offset the real property tax increases, and possibly do more. And the Schedule H model is demonstrably administrable. However, the policy logic does not follow from households to businesses. The benefit will be available to all small retail businesses regardless of the soundness of their business practices. In some cases, it will be a life line for small businesses. In others, it will subsidize poor business models that cannot generate sufficient income.

Targeting retail only is also distortionary, since it is not clear why a small business engaged in retail is a worthier cause for a tax break than a restaurant or small businesses providing a myriad of other services. It is possible that the Council proposal could be covering more than retail: the estimated number of establishments that will benefit (4,400) is greater than what the County Business Patterns data show to be the number of retail establishments in the District (a total of 1801 in 2016, and only about 1,300 with fewer than 10 employees—a group much more likely to have gross receipts under $2.5 million). Perhaps the Council envisions that the credit will be available to all small businesses so long as they are engaged in some type of retail, such as yoga studios that sell yoga mats or garments, or hair salons that also sell hair products.

While the budget proposal increases commercial property taxes, it also offers a handful of tax abatements and tax incentives. These proposals might be supporting organizations with worthy causes and initiatives with important economic impacts. Nonetheless, this a la carte tax policy increases the complexity and reduce the equity of the tax code. To be sure, these tax incentives do counteract the impacts of the proposed commercial property tax increase, but only for those who have managed to pass a legislative hurdle.

The budget proposal will further widen the gap between the tax treatment of commercial and residential property classes.

On the residential side, the mayor proposed (and the Council went along with) a proposal to reduce the real property tax cap on how much taxable assessments, and therefore tax bills, can grow. At present, residential tax bills cannot grow by more than 10 percent regardless of how much the market value of a property has increased. Under the budget, this cap will be reduced to 5 percent for middle or low-income seniors.

Tax preferences for seniors are popular across the country because seniors can be a strong political force. Still, this proposal further increases the wedge between the tax treatment of commercial and residential properties, deeply impacting future growth patterns. The District has the lowest residential property tax rate and the lowest residential property burdens in the Metro area. The burdens are particularly low because, combined with the homestead deduction, the tax cap reduces the rate, according to my estimates, from the statutory 0.85 percent to an effective 0.65 percent across the city. For certain seniors, the effective rate will now be even lower.

Elsewhere in the budget, the city shows great effort to increase housing affordability through expanded expenditures. But the proposed reduction in the cap will achieve exactly the opposite. Low property taxes help current owners. But because of the restricted housing supply in the District, much of the preferential tax treatment for homeowners simply results in higher prices for consequent buyers, creating a windfall when current homeowners sell their homes to move elsewhere. (California’s Proposition 13, which allows for zero growth in taxable assessments, is the extreme example with deep impacts on housing prices that proved to be a boon for the rich, and a trap in municipal finances; recent research shows that SALT deductions end up increasing prices in constrained housing markets).

Furthermore, the property tax cap becomes problematic during downturns. Recessions erode the value of housing and can cost residents their jobs and incomes, but tax bills continue to increase to catch up with housing value growth in pre-recession years. This causes pain exactly at the wrong time.

The budget will tax the same service at wildly different rates.

The last component of the Metro funding is a tax on ride sharing companies. At present, ridesharing companies pay a gross receipts tax of 1 percent. Taxicabs offer the same service but do not pay a gross receipts tax. Instead, they send the District a 25-cent surcharge they collect from the customers for each ride, which is not added to the bottom line, but is dedicated to the agency that regulates vehicles for hire.[2] Looking at meter data, the D.C. Policy Center estimates that under the current regime, taxicabs send about 2 percent of their meter fare to District coffers whereas ridesharing companies such as Lyft and Uber send only 1 percent. The Mayor’s proposal included a rate hike proposal for ride sharing companies only, bringing their gross receipts tax to 4.75 percent. The Council has proposed to increase it to 6 percent.

One can argue, as the Council’s budget documents do, that the 6 percent rate makes sense because it taxes ridesharing services at the same rate as other services, which are subject to the general sales tax per the recommendations of the second Tax Revision Commission. But if that is the case, why are taxicabs, which provide a very close substitute, taxed at 2 percent? Others argue Lyft and Uber should pay for the Metro because they compete with Metro, or because they use public roads and therefore should pay for the wear-and-tear and congestion they cause as well as for their environmental impacts. All these arguments equally apply to taxicabs.

Taxes pay for important investments; this is even more the reason to prioritize sound tax policy.

Tax increases proposed by the mayor and the Council pay for important investments in DC residents and the city’s infrastructure. This year’s budget supports critical investments in the Metro, and provides additional funding for housing, education, and programs to counter homelessness. These are worthy causes deserving of public support.

But the way the budget proposes to generate revenue does not serve the best interests of the District of Columbia. And its revenue initiatives sometimes counter the goals the budget tries to achieve on the expenditure side. These conflicting policies cause the city to spin its wheels in important issues such as housing affordability and increasing economic activity, and they impose a pure cost on future growth.

The District needs no reminder that public investments can continue to increase only if the city continues to grow. And poor tax policy that does not sufficiently weigh the importance of economic growth will frustrate government investments.

While the city’s commitment to good tax policy through periodic review and reforms is commendable, what happens in between can use improvements.