Urban planners and local governments attach great value to cultivating neighborhoods where residents are close to public transportation or can walk or bike to work. D.C. has also adopted this approach. The city has built over 70 miles of bike lanes, passed a rigorous law to protect bicyclist and improve pedestrian safety, implemented the Vision Zero program to reduce pedestrian fatalities, developed a long-term transportation plan with heavy emphasis on walking, biking, and living close to work, and even piloted a home purchase assistance program for people who will move into the city to live near their workplaces. Whether because of these programs or by sheer number of people who have moved into the central corridor, the city has become more walkable and bikable. One website ranks the District 7th among cities with a population of 500,000 or more both in walkability and bike-friendliness.

Walking and biking is one of the benefits of city living, but for some, it is a sign of future displacement

As Steve Swaim at District Measured has shown, housing prices in D.C. increased much faster than the prices in the metropolitan region and also much faster than the median income in D.C.—meaning that D.C. residents of all income levels are spending an increasing share of their incomes on housing. The relative as well as absolute rise of housing prices affects low-income residents most of all, and contributes to their displacement from neighborhoods that see property values rise the most.

Policies that promote walking, biking, and living near public transit do not offer relief from these trends, as the most economically vulnerable residents of the city live too far from their places of work to walk or bike. In fact, these policies may be hurting our poorer residents: Recent research shows that transit-oriented development programs can create social inequities and increase the pace of gentrification, and there is already evidence that this has been happening in D.C., as Martin Di Caro explored in a two-part series (1, 2) on transit-oriented policies and gentrification in 2012.

Policies meant to make the city more walkable and bikable can be perceived to amplify transportation injustices—or, at a minimum, change how these communities function. And the communities at risk for displacement because of gentrification speak out against them. Bike lanes, for example, have been a frequent point of contention with some of the fiercest resistance coming from churches serving D.C.’s African American communities, who want to maintain Sunday parking for suburban parishioners. For parishioners, these churches anchored their communities during some of the District’s toughest years, and investments in bike lanes can be seen as mechanisms of displacement imposed on these neighborhoods after years of neglect. Proponents argue that all residents can benefit from safer bike lanes and reduced traffic congestion.

People’s perceptions should not be the basis of policy, so we turn to data.

Demographics of who walks and bikes to work

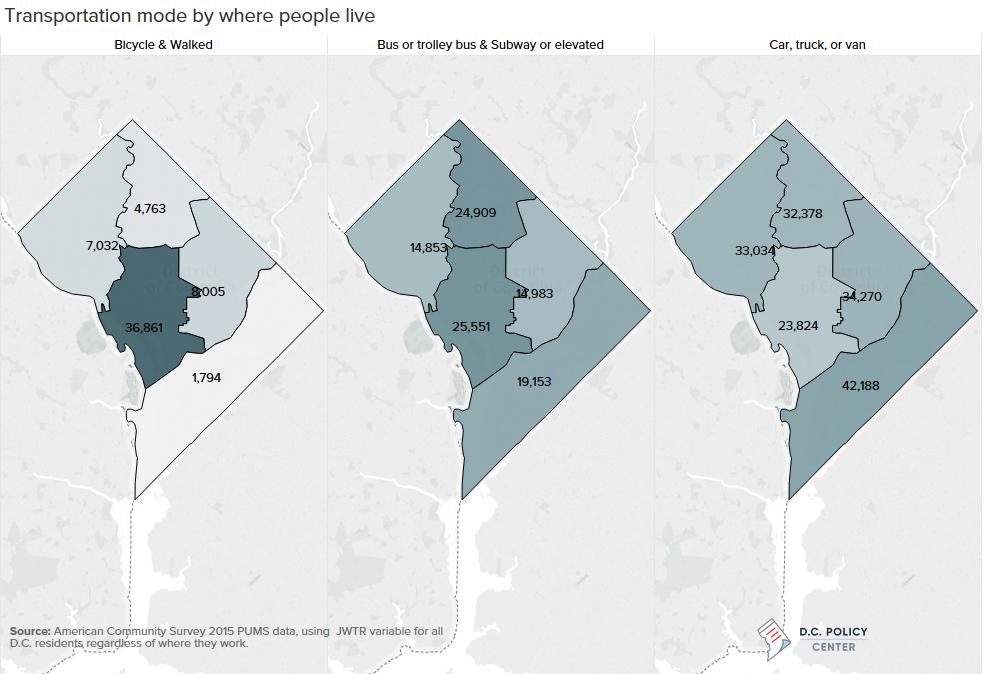

While correlation is not causation, the data tell us that where you find walkable, bikable communities, you also find gentrification. Consider commute modes by where people live in the city: According to American Community Survey estimates for 2015, District residents who bike or walk are clustered in the city center (nearly 37,000 in number), while only a small fraction of residents east of the Anacostia River (fewer than 2,000) walk or bike to work. This is not a surprise—those who live in the city center are also close to job centers, while most residents east of the river work outside of their neighborhoods, and most likely outside the city.

The heaviest use of buses and Metro occurs within the central corridor, where public transportation networks are densest. More residents east of the river drive to work than any other section of the city, despite low access to cars. That is, east of the river residents have few options to go to work because their employment opportunities are much further away from where they live. In these neighborhoods, over a third of the residents face commute times of 45 minutes or more. (Communities to the west of Rock Creek Park are disadvantaged purely in terms of this public transportation metric because metro presence is scarce, but their commute times remain relatively short.)

Those who can walk and bike are also those who can afford to live in the central corridor

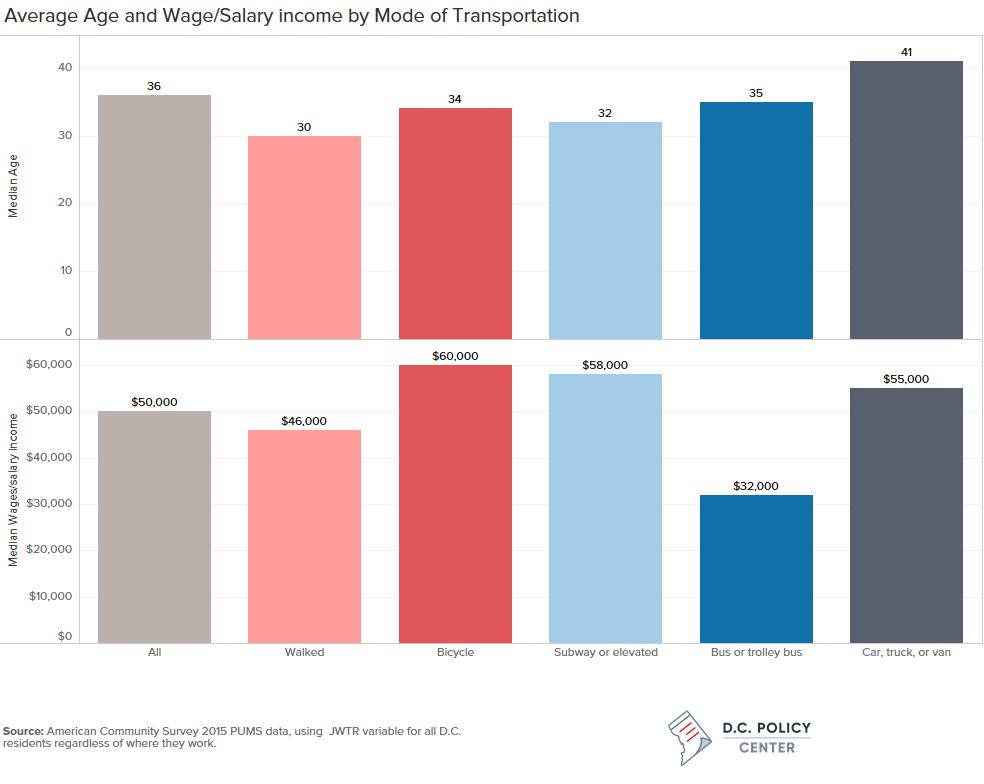

In 2015, the median age of D.C. residents in the workforce was 36, and median salary or wage income was $50,000. People who walked to work were much younger (median age of 30) and earned slightly less than the median salary ($46,000) than the typical D.C. resident. People who biked to work were also younger, but earned more than the median salary ($60,000). Those who took the bus, on the other hand, were at about the median age (35), but earned substantially less ($32,000). Those who drive earned slightly more than the median wage, but were considerably older (median age, 41).

If we were to adjust for age differences, we would find that those who walk and bike to work are richer than those who drive or take the bus. That is why they can afford to live close to where they work.

There is a deep racial divide in commuting modes

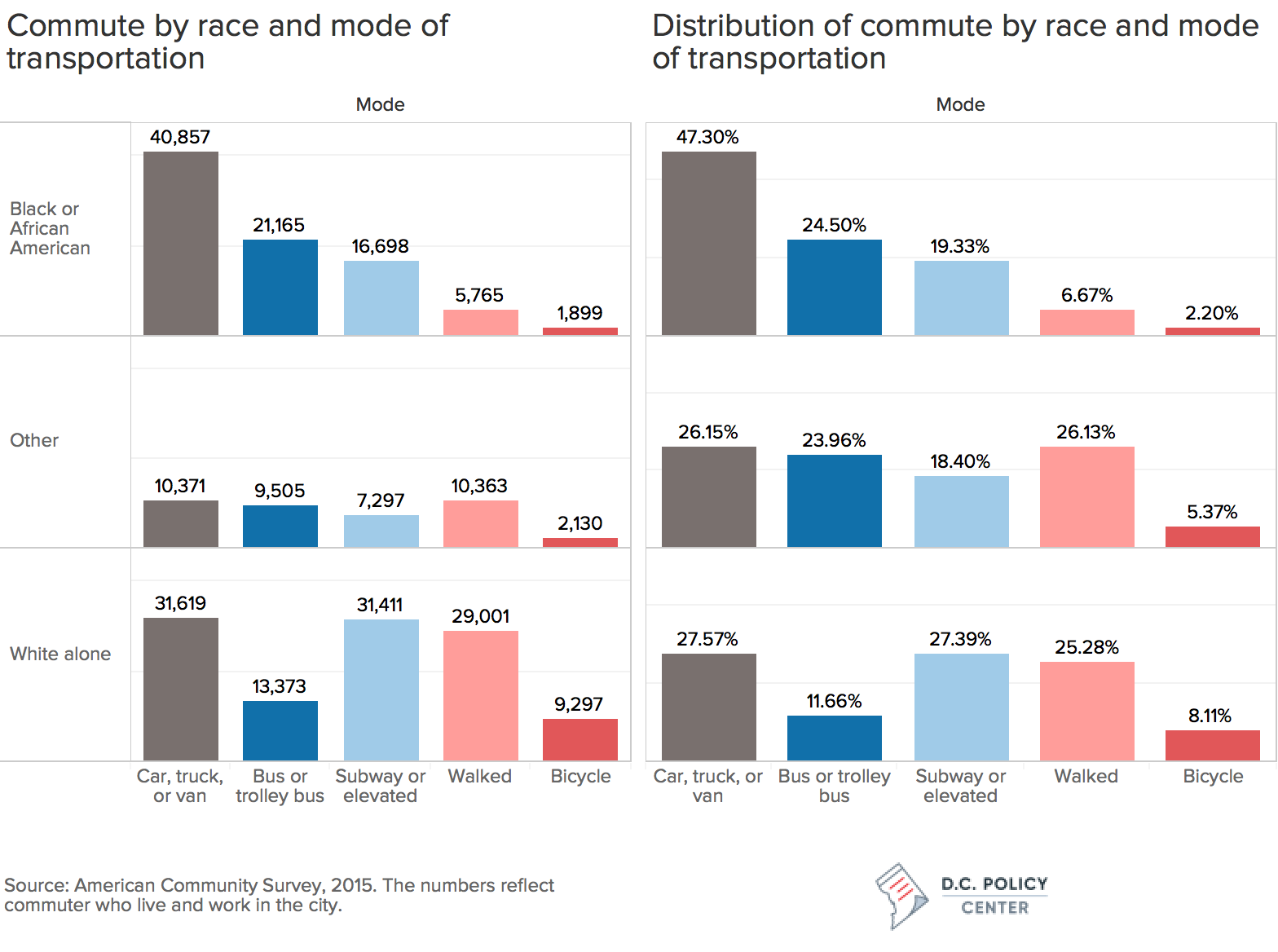

Breaking the same data by race, we see that D.C.’s black residents are more likely to drive to work. Among D.C. residents who work in the city, nearly 41,000 blacks drive to work compared to 32,000 whites. When it comes to public transportation, whites more frequently take the Metro; blacks more frequently take the bus. Only 5,765 black of African American residents walked to work in 2015, compared to 29,000 whites. Only about 1,900 black or African American residents biked to work; this is one fifth the frequency among whites.

In shares, 47 percent of blacks drive compared to 27 percent of the whites, and only about 8 percent of blacks walk or bike to work compared to 33 percent of the whites.

What is the policy takeaway from all this?

There is a proposal at the D.C. Council to expand transportation benefits to those who walk or bike to work. Specifically, this proposal will require businesses to offer walkers, bikers, and public transit users the cash equivalent of parking benefits that businesses offer to those who drive. The arguments are well-intentioned (less congestion, better health, cleaner air), but social injustice will increase as a consequence. If firms were forced to offer cash to those who walk or bike, they would be forced to increase the salaries of those who already earn more than the rest of their workers. And this will come at a cost to those who have no other option but to drive.

If we truly want to make D.C. a more walkable, bikeable, transit-friendly city, we should start with our broader housing and transportation policies. We should expand D.C.’s stock of affordable housing and promote dense, mixed-income developments along transit-accessible corridors; improve both Metro and bus networks so that they are an accessible and reliable option for all residents. And—in conjunction with these measures—we should continue to improve streets for pedestrians and cyclists, so that residents of all neighborhoods can safely access these healthier modes of transportation.

To be clear, bike lanes are good. Safe sidewalks are good. They are relatively cheap investments that reduce congestion and help improve health. But beyond investing in infrastructure and improving safety, D.C. Government does not need to favor those who walk or bike to work. And it should not favor those who drive either.

We don’t have to don a veil of ignorance to formulate transportation policy. Those who can walk or bike to work have already won the income lottery.