Prior to the Revitalization Act, D.C. Code offenders served their sentences at the Lorton Correctional Complex, a medium security prison for convicted felons outside of D.C. In oral histories recorded in 2013, D.C. Code offenders often mention that the proximity of Lorton to the District of Columbia allowed them to maintain ties to the community and be able to continue their relationships with family and friends.1

After the Revitalization Act, Lorton was closed, and D.C. Code offenders were transferred to various federal facilities around the country. The transfer occurred in three stages, with the first prisoners transferred in March of 1998 and the last transferred in November of 2001.2

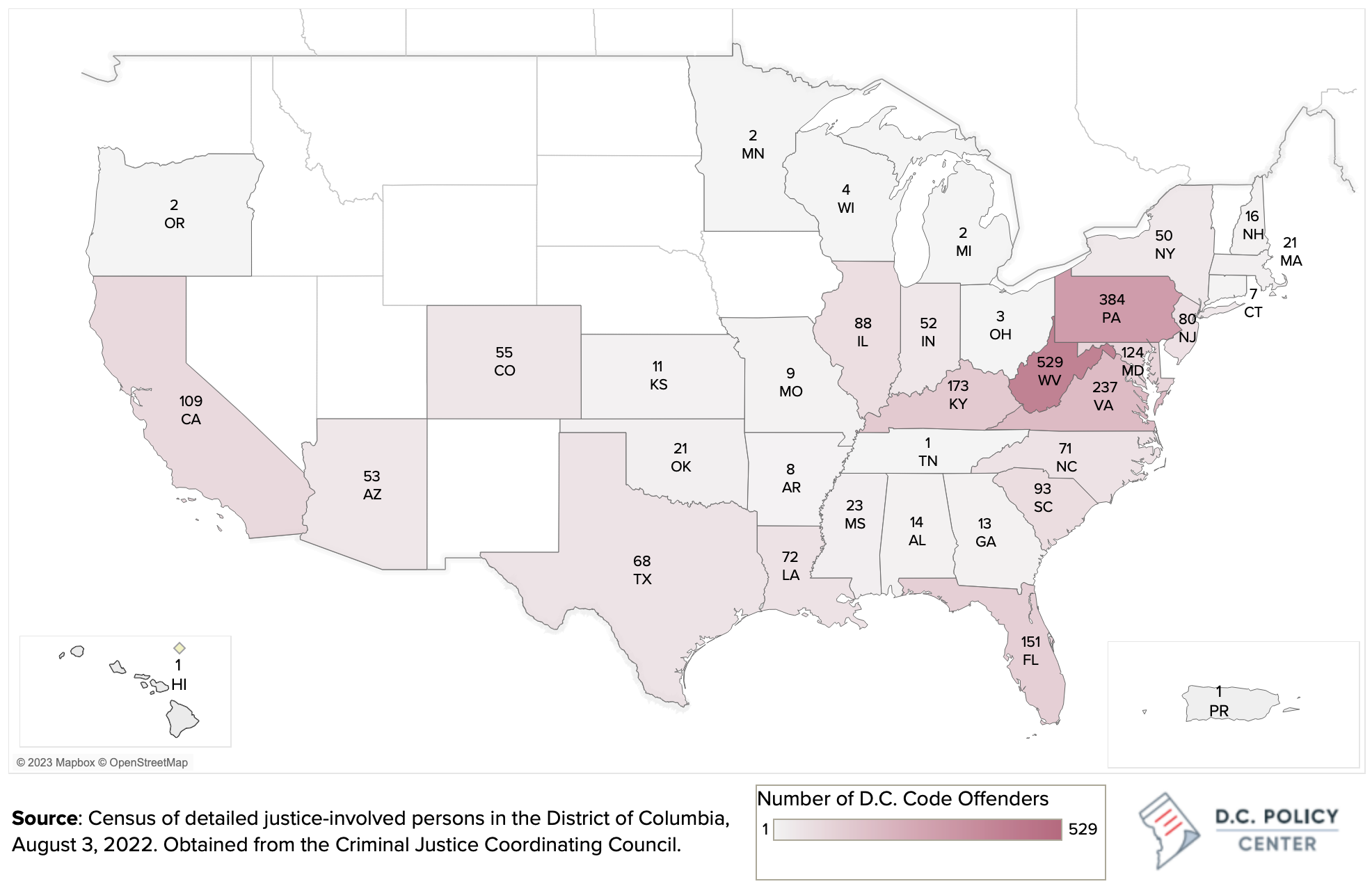

The Revitalization Act requires D.C. Code offenders to be jailed within 500 miles of D.C. “to the extent practicable” (this is a standard BOP policy that is not specific to D.C., which has been codified under the First Step Act).3 However, according to BOP data, more than 45 percent of incarcerated D.C. Code offenders are further away.4 Incarcerated residents can be held at any of the 122 facilities that BOP operates, as far away as California, Hawaii, or Puerto Rico.5

D.C. Code offenders are held farther away than their peers in other states

The average distance between D.C. Code offenders and their communities and families is farther than the average distance in other states. The average distance between D.C. and D.C. Code offenders in BOP facilities is 818 miles.6 While there is no recently available data on the U.S. as a whole, one study from 2001 found that the average distance between an incarcerated male and his home or family is 100 miles across all states, and the average distance between an incarcerated female and her home or family is 160 miles.7

Impacts of this distance disparity

D.C. Code offenders being incarcerated far from D.C. can have negative consequences. Urban Institute research has shown that in-prison contact with family members is a predictor of strong family relations after release and lower recidivism rates.8

Additionally, being out-of-state during incarceration may result in disruption of certain services. For example, D.C. Code offenders who are incarcerated at the D.C. Jail can have Medicaid coverage suspended instead of revoked, and automatically reinstated upon their release. In contrast, when D.C. Code offenders are incarcerated in BOP facilities, they must reapply for benefits, and could therefore experience gaps in health care coverage.9

No other state has a similar arrangement with the Bureau of Prisons, so it is difficult to compare the incarceration experience of D.C. Code offenders to code offenders in other states. However, several key characteristics of D.C. Code offenders in the federal system have large impacts on the experience of D.C. Code offenders and can have serious consequences, including distance from community and family, the differences between the characteristics of D.C. code offenders and federal code offenders under BOP custody, and the availability of and access to rehabilitation programs for D.C. code offenders.

Differences in age, sentence type, and sentence length between D.C. Code offenders and federal code offenders influence the security levels of facilities D.C. Code offenders are held in, and therefore their access to rehabilitative programming, where in the country they are held, and their level of confinement while incarcerated.

Additional information about the history of D.C.’s criminal justice system and known information about how the system currently functions can be found in the main text of our report.

About this series

This publication is part of the D.C. Policy Center’s Criminal Justice Week 2023, which explores various aspects of the District’s criminal justice system. Other publications in this series include:

- How D.C.’s criminal justice system has been shaped by the Revitalization Act

- Processing through D.C.’s criminal justice system: Agencies, roles, and jurisdiction

- A look at who is incarcerated in D.C.’s criminal justice system

- How much would it cost to build and maintain a new D.C. prison?

These publications are adapted from The District of Columbia’s Criminal Justice System under the Revitalization Act: How the system works, how it has changed, and how the changes impact the District of Columbia, commissioned by the District’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

Endnotes

- Lorton Prison Stories Project (2014). Available at https:// lortonprison.blogspot.com.

- When this transfer was completed, there were 6,082 D.C. Code offenders under BOP custody. This group collectively made up 4 percent of federal prison population. For details, see Roman & Kane (2016).

- Some D.C. Code offenders are more likely than others to be housed more than 500 miles away, due to specific needs of D.C. Code offenders and availability in federal facilities. People more likely to be housed further away include inmates with significant medical needs who must be placed in our Federal Medical Centers, special management inmates (for example, inmates requiring protective custody); and ’discipline cases’. Lappin, H. (2010), “Housing D.C. Felons Far Away From Home: Effects on Crime, Recidivism, and Reentry.”

- Calculation based on locations provided in the Census of detailed justice-involved persons in the District of Columbia, August 3, 2022. Obtained from the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

- According to the most recently available data, federal prisons and contract facilities in West Virginia hold the largest number of D.C. Code offenders, followed by Pennsylvania. These are followed by facilities in North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, South Carolina, New Jersey, Florida, Maryland, and California.

- This number is an average of distance between the locations of D.C. Code offenders in BOP facilities, weighted by the number of D.C. Code offenders in each BOP facility. The average distance between D.C. and the BOP facilities (not weighted by the number of D.C. Code offenders in each location) is 1,400 miles. The names of BOP facilities and number of D.C. Code offenders in each facility were acquired from the census of detailed justice- involved persons in the District of Columbia, obtained from the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council in August 2022.

- This is a widely cited statistic, but the original estimate can be found in Hagan & Coleman (2001).

- La Vigne, N. (2014), “The cost of keeping prisoners hundreds of miles from home.”

- D.C. Legislation from 2015 allowed for the” suspension of coverage” while a person is incarcerated rather than “termination”. DOC sends a list to the Department of Health Care Finance, which manages Medicaid, monthly to let them know about people being released. When people are released, their status is changed back to active and they can immediately access health insurance. BOP does not release lists of people being released, and thus local agencies are not notified to restart service provision. Council for Court Excellence. (2016). “Beyond Second Chances – Returning Citizens’ Re-Entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”